Fishing was pretty good over the weekend, with tog and sea bass caught from boats sailing from Lewes and Indian River. The strong current supplied by the new moon made it difficult to keep bait in the strike zone, but in spite of the conditions, limits of sea bass and tog to over 12 pounds were caught.

Closer to shore, Indian River Inlet continues to give up the occasional rockfish, with flies fished behind a sinker the most successful offering. The few anglers with live spot remaining in their live wells did manage a few keeper rockfish while drifting the inlet.

On the surf, the dog sharks and skates have taken over. I did have a report of one or two rockfish caught on frozen bunker from the beach at Fenwick Island.

I understand a few boats were seen fishing Fenwick Shoal for rockfish. The shoal is well beyond the state’s three-mile limit, and fishing for striped bass is prohibited in federal waters. Should you be caught, the case will be heard in federal court, and the recent guilty plea by a charter captain to charges under the Lacy Act may result in jail time, a big fine and loss of his boat. Is catching a few fish really worth the risk?

The striped bass young of the year

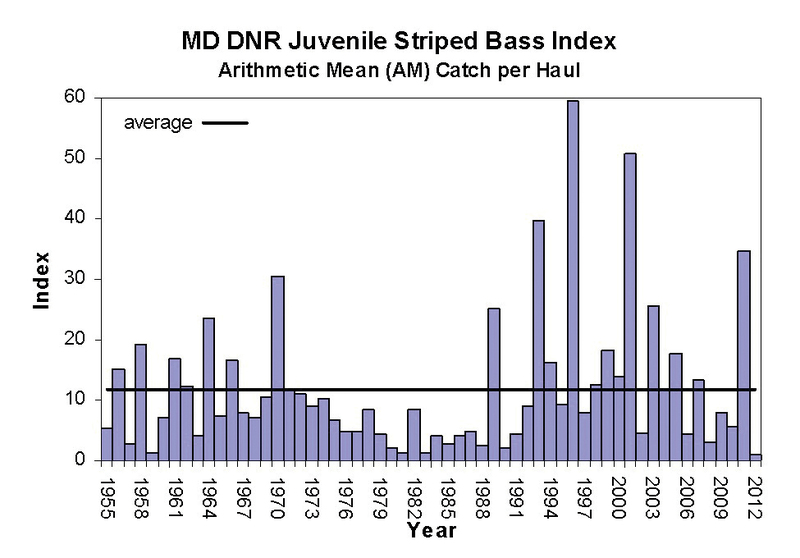

The state of Maryland has surveyed the young of the year striped bass population since 1955. They haul seine various locations, count the number of striped bass at each site and then compile the results. In 2012, the survey recorded its lowest number on record. The YOY was 0.9, meaning on average, less than one striped bass was caught at each site.

Delaware does not conduct a targeted striped bass YOY survey, but these fish are counted as part of the annual trawl survey. New Jersey does count young of the year rockfish, but those results have not been released. Virginia reported its survey was as poor as Maryland’s.

So what caused this drastic decline in young of the year numbers? The answer may lie in the drought we experienced last winter and spring. The Delaware trawl survey did not record any striped bass fry until it reached the northernmost location in the Delaware River. Maryland indicated it too had saltwater much farther up the bay than is even close to normal. This high salinity would make it very difficult for the fry to survive.

We know that the condition of the water in the upper reaches of the bays and rivers where striped bass spawn is critical to their survival.

When you examine the results of the YOY survey in Maryland, you can see it is made up of highs and lows. There were several above-average year classes from 1955 to 1970, and then a series of below-average classes from 1971 to 1989. Those 18 years of low spawning success resulted in a decline in the striped bass stock to the point of collapse. The striped bass moratorium stopped the harvest of these fish all along the coast. To the surprise of those who opposed this action, once we stopped killing rockfish, they made a remarkable comeback.

In 1989, there was a YOY index that was high enough to trigger an end to the moratorium. The addition of Hambrooks Bar to the list of survey sites was the reason for this better-than-average result. It was the only location that had a count above the average, and it was so high, it brought the overall level to a point higher than anything since 1970. While it was never proven, some of us thought politics might have had a hand in the addition of Hambrooks Bar to a list that had remained the same since 1955.

In the mid-1970s, a State-Federal Advisory Committee was formed to examine the plight of the striped bass. I represented Delaware recreational fishermen, and Roy Miller was there from the Division of Fish and Wildlife. We fought an uphill battle for years trying to come up with regulations that would halt the decline, with very limited success. Finally, Congress gave the Atlantic States Fisheries Advisory Commission the power to enforce regulations, but by then many of us felt a moratorium was the only solution. It was Gov. Hughes from Maryland who ordered a complete moratorium, and Delaware followed shortly thereafter. Other states implemented their own moratoriums, and even the Commonwealth of Virginia was dragged kicking and screaming into compliance.

Today the ASMFC has regulations to prevent a repeat of the decline in the 1970s and '80s. Should the YOY fall below average for three years, regulations would be reviewed and strong actions taken. Let’s hope that doesn’t happen.