Lewes artist Tom Wilson celebrated in new documentary

Inspiration to make a film about Lewes artist Tom Wilson struck documentarian Warren Lewis Allen in a most surreal way.

“Last winter, I had a dream Tom’s paintings were talking to me,” Allen said. “I was kayaking in the marsh, and one of his paintings told me to make a film. I thought about it for a while to make sure it was something I wanted to do.”

Painter and photographer Tom Wilson died in 1995 of complications from AIDS in his Lewes Beach home.

Allen, who is now living in Los Angeles, grew up in Seaford and Rehoboth, where his parents befriended the artist and joined a close circle of friends that included Back Porch Cafe co-owner Keith Fitzgerald and Nassau Valley Vineyards owner and singer Peggy Raley-Ward. Allen himself was painted three times as a child by the prolific artist.

Allen said he called Fitzgerald last March. “He had been talking to my mom about writing a book about Tom,” Allen said, and it became more and more apparent that it’s time to make a film.

Since Wilson’s death, Fitzgerald has stored a museum’s worth of his artifacts: unfinished works, photos, early negatives, poetry, notebooks, a list of customers and other documents - everything right down to the paintbrushes he used. Wilson’s work has never been catalogued in print or online.

“We all started thinking about preserving his legacy,” Fitzgerald said on a warm, early spring morning on his restaurant’s back porch.

Allen, Milford native and cinematographer Skylar Wilson (no relation to the artist) and Nashville sound-mixer Daniel Maxwell Davis traveled to Sussex in late March to interview local art collectors and Wilson’s friends for a short documentary on his life and work. Allen hopes to complete the film by the fall and submit it to the festival circuit, including Rehoboth Beach Independent Film Festival, as well as online streaming services to gain financing for a feature-length movie. This will be Indiana Avenue Filmmakers Collective’s fourth film, as yet untitled.

After graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1969, Wilson moved to New York City to paint. Soon afterward, a friend invited him to an Andy Warhol party.

“The whole New York City art crowd was there. He met photographer Francesco Scavullo, who was, like most people, taken by the man’s beauty. Soon Tom had modeling agents knocking on his door,” Fitzgerald said.

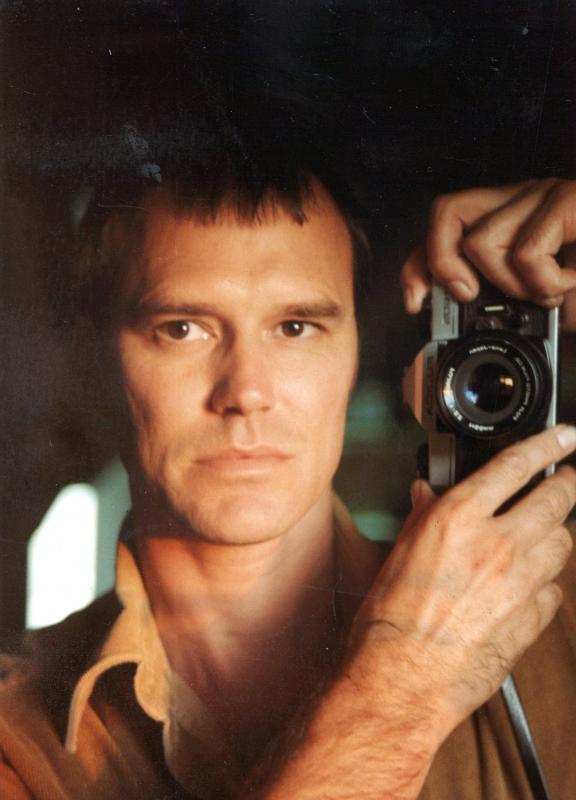

And with that, Wilson became one of the top fashion models of the ’70s, photographed by prominent artists Scavullo, Fred Eberstadt and Richard Avedon for Vogue, Cosmopolitan, Harper’s Bazaar and Time magazines.

“He had a phenomenal career and worked all over the world for several years. He didn’t talk much about it; in fact, it was years till he showed us his portfolio. He called that career ‘other things.’ He said he made his living at ‘other things,’” Fitzgerald laughed.

“Modeling financed his ability to stay in Paris and work on his art,” Raley-Ward said. “His father wanted him to become a lawyer in the family firm, so he got no support from them. He was literally the starving artist in Paris. Modeling was just a means to an end for him.”

In 1981, Wilson left Paris and New York City for his hot-pink Lewes studio, set among the irises, lilies and ponds behind his parents’ Indiana Avenue beach home.

“The Eastern Shore was in his blood. His family was here for 300 years,” Raley-Ward said. “It was natural for him to return here to capture the light, the people and their relationship with the land as a subject for his paintings.”

“He was a master of light. Sussex County seems to have a light to it at certain times of the year. It’s just magical and not like any place else, and Tom loved it. He worked from photographs - he took boxes and boxes of photographs of Sussex County light that he was able to translate onto canvas by tweaking shadows and shortening and lengthening perspective, which was a pretty amazing skill,” Fitzgerald said.

Fitzgerald recently found in storage a black, 1-inch binder labeled “press” in green on faded tape. Wilson’s personal clippings binder contains yellowed, photocopied magazine and newspaper articles, and a typed explanation of his own work by the artist: “I like to play with light in my paintings, and to make fantasy combinations by putting figures in situations they never were actually in. Sometimes I have several light sources and leave out certain shadows which gives a vaguely surreal feeling.”

When Wilson returned to Sussex County in the early ’80s, Rehoboth Beach was still a largely seasonal resort, much different than today. The gay and lesbian community was just beginning to come out. That era also saw the birth of Rehoboth’s fine-dining scene, drawing foodies from all over to now-legendary restaurants like the Back Porch Cafe, Chez La Mer and Blue Moon.

“Tom came into the restaurant initially as a customer,” Fitzgerald said. “He loved to eat and appreciated good food, and he was interested in who created the cuisine. When he was introduced to Leo, it was love at first sight.”

Long-time Back Porch chef and co-owner Leo Medisch enjoyed a 13-year relationship with Wilson. Medisch died of lung cancer in August 2013.

“There was such an energy with Leo and Tom. It was like they were made for each other. Leo was an artist in his own right - a culinary artist. A love of food and travel bonded them, and I think they realized that right out of the gate. But, I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who met Tom in person and didn’t fall in love with him,” Fitzgerald said.

With both culinary and traditional artists working at the Back Porch, the restaurant was already hosting art shows for friends and employees.

“It was a natural progression for Tom to fall in with us. He was already an established artist - he had studios in Europe and New York City - and he asked if he could have a show at the Back Porch. His show was hugely popular and well-attended,” Fitzgerald said.

This success led to Wilson’s appointment as Back Porch Cafe’s art director. He organized four to five shows a summer, including one of his own every year, where Wilson’s commissioned paintings would net $20,000 each, sometimes more. Once a student of Lewes artist Howard Schroeder, Wilson also taught a number of local artists in his Nassau Commons and Lewes Beach studios and local art galleries.

“He didn’t like the formality of the art world, so he broke away from the big galleries. His art was good enough that he could represent and sell pieces on his own; he had a backlog of customers waiting for commissions. For several years after his death, patrons still returned to the Back Porch to commission his work. We had a couple shows after he died, and his work commanded the same prices as when he was alive,” Fitzgerald said.

Wilson is perhaps best known for his use of oils in warm portraits, pastoral scenes and area houses that engage the viewer by combining everyday scenes with surreal elements and evoke the interpretive realism of painter Edward Hopper. While in Paris, he experimented with a form of pointillism using paint and embroidery to create art with dots of different colors and abstract patterns.

“All phases were expressions of who he was,” Raley-Ward said.

Raley-Ward grew up on Lewes Beach, close to Wilson. “I remember the first time I met him. I was 13. He came to the door wearing overalls and no shirt; he was a stunning figure. I didn’t know who he was. It was like Adonis was standing at the door, and I thought, ‘Thank you, God!’”

He and Raley-Ward bonded over a love of music.

“Tom tuned into what value you found in art. Once he learned how much I loved jazz, he took it as his duty to educate me. He had thousands of records and cassettes, and I listened till my ears fell off. I spent hours discussing music with him. He wanted to know how the music emotionally changed me, how it inspired me. He loved that I loved music, and it made us compatriots. It didn’t matter that I was 13. I was worthy to receive the education of music from him. He fed my head.”

Raley-Ward said Wilson didn’t paint without music playing.

“For him, the type of music was very important in terms of where he was in the painting. Music was as much a mood as the colors he was working with. The music playing was indicative of what was coming out of his fingertips,” she said.

At 5 p.m. every evening, friends would gather at Wilson’s house for cocktails in cut crystal glasses and Medisch’s gourmet offerings plated on elegant china.

“He attracted artists and those with artistic temperaments - people who loved life. I always said he went from a fashion plate to a fashion platter with Leo, he enjoyed his cooking so much,” Keith smiled.

Then came HIV and AIDS.

“We were losing people left and right to AIDS. Over a five-year period I went to 30 funerals,” Raley-Ward said.

“With no medication for it, learning you had HIV was basically a death sentence in those days,” Fitzgerald said. “It was a foregone conclusion he was going to die, but he chose to focus on the time he had. Tom lived in the moment and enjoyed life while he was here. He didn’t know until close to the end how much time he had left.”

Wilson worked until he no longer could. As his health declined and vision dimmed, he focused on pastels and small, colored-pencil drawings.

“You could see in them the darkness, because that’s what he saw,” Fitzgerald said.

His last project in oils was to be a set of six paintings of his family’s Prime Hook Neck property, Fairfield Farm, from the point-of-view inside a stable as light filters through the barn wood cracks. He finished only two before his death.

“He was a beautiful spirit, a beautiful man,” Fitzgerald said. “Great art is always great, and I don’t see any reason Tom’s art won’t live on.”

Follow the documentary’s progress on Facebook at ‘Untitled Tom Wilson Documentary.’