Wetlands in the Broadkill River watershed are disturbed, reducing their ability to absorb storm surge, prevent flooding and improve water quality. But all is not lost; a recent watershed health report card gives the watershed a grade of C.

State environmental officials have developed a list of nine recommendations to improve wetlands in the watershed; at the top of the list is protecting nontidal wetlands, which are not protected under state law.

Tidal wetlands, making up nearly half of all wetlands in the watershed, received the lowest grade: D+.

The Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control wetland monitoring and assessment program survey found that 65 percent of the watershed's three wetlands – flat, tidal and riverine – were moderately disturbed. That's a higher percentage than the nearby Inland Bays – 43 percent moderately disturbed – and Murderkill River – 46 percent moderately disturbed.

Alison Rogerson, program manager, said moderately disturbed wetlands continue to function, but they are under threat. She said researchers were surprised to discover that such a large percentage of the watershed's wetlands were disturbed.

“Most are in the middle of the road. There is a lot of room for improvement, but it's not a lost cause. There are not a lot of wetlands in the bottom [worst] category,” she said.

Rogerson said the major factors affecting Broadkill wetlands include: ditching and drainage; development too close to wetlands; timber harvesting and the spread of invasive species. The watershed has lost about 14 percent of its wetlands, the report shows.

She said development in the watershed is occurring right at the edge of wetlands. “With a nice, wide buffer the wetlands would work better,” she said, adding the same holds true for farm fields.

Sea-level rise is another factor facing the watershed. State scientists say even with a modest rise of 1.5 feet over the next 90 years, models predict 98 percent of the area's tidal wetlands and 9 percent of nontidal wetlands would be inundated.

Buffers: A hot topic in Sussex

Buffers, such as those recommended in the study, are a hot-button issue in Sussex County.

Recent regulations to increase buffer widths in Sussex County were included in the Inland Bays Pollution Control Strategy, but the county challenged DNREC's right to establish buffers.

A 2011 Delaware Supreme Court decision struck down a regulation in the Pollution Control Strategy requiring 100-foot buffers designed to reduce runoff and pollution from development into the inland waterways. The ruling also did away with DNREC's power to enforce wider buffers in specific cases. County code requires no more than 50-foot buffers.

"DNREC lacks the statutory authority to engage in zoning practices; DNREC exceeded its powers in enacting the PCS regulations," the ruling stated.

Wetlands are important because they help filter pollutants, provide habitats and nurseries for fish and animals; enhance recreational opportunities; help improve water quality flowing into streams and rivers and hold stormwater during periods of heavy rain and floods, Rogerson said.

“When wetlands are pushed to their limits, they do not do everything they could,” Rogerson said.

She said coastal wetlands are critical to protect property and quality of living because they soak up storm energy. She said areas with thriving coastal wetlands helped reduce Hurricane Sandy's storm surge from 9 feet to 4 feet.

Improving the watershed

According to the report, establishing and enforcing wetland buffers that start at wetlands' edge would improve the wetlands and water quality. Wetland and riparian buffers with forested vegetation would maximize nutrient removal from groundwater, surface water runoff and in-stream flow, while improving corridor habitat, the report notes.

The spread of phragmites, a nonnative, invasive plant, continues to be a problem for tidal wetlands. Because phragmites spreads rapidly, outcompeting native species, the report states, it reduces plant diversity in undisturbed areas and reduces the success of other organisms by changing habitats and reducing available food.

The DNREC Phragmites Control Program in the Division of Fish and Wildlife has treated more than 20,000 acres on private and public property since 1986. “Without continued support from state funds and federal State Wildlife Grant funds, phragmites will degrade more wetlands,” the report states.

If phragmites were eradicated, only 3 percent of the tidal wetlands in the Broadkill River watershed would be severely stressed – down from 14 percent – according to the report.

Rogerson said of the nine recommendations, protecting nontidal wetlands would most benefit the Broadkill watershed. Nontidal wetlands fall under the jurisdiction of the Army Corps of Engineers and not the state.

The nine recommendations are:

• Improve the protection of flats, inland wetlands that feed coastal streams.

• Improve protection of nontidal wetlands with a state regulatory program in concert with county and local governments to reduce the ambiguity surrounding which wetlands are regulated. In Sussex County, nontidal wetlands extending 50 feet from a perennial stream are not protected.

• Improve nontidal wetland buffer regulations and codes working with state and county officials.

• Update tidal wetland regulatory maps.

• Develop incentives to encourage property owners to maintain natural buffers of tidal wetlands.

• Control the extent and spread of phragmites.

• Improve enforcement of wetland permitting and mitigation monitoring.

• Design a wetland restoration plan for the Lower Delaware Bay Basin that includes the Broadkill River watershed.

• Support Delaware's Bayshore Initiative by securing funding for wetland restoration and preservation

Environmental officials recommend that landowners plant and maintain buffers and rain gardens on their land; remove invasive species on their property and replant native species; and fill in ditches and/or reroute ditches to mimic natural stream flow.

Rogerson said the report is not the final phase in the process. She said the final step will be to develop a watershed restoration plan and prioritize how funding should be spent.

For more information, go to delawarewatersheds.org or dnrec.delaware.gov.

Broadkill watershed covers 68,000 acres

During the summer of 2010, a team of DNREC wetlands scientists visited 94 wetland sites in the watershed and collected data on plants, hydrology and wetland disturbances.

Changes documented in the 67-page report include: Conversion of 75 acres of freshwater wetlands into development or farm production; a substantial loss of coastal wetlands in Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge and Broadkill Beach to development and conversion to open water from breaches in the duneline at Fowler's Beach; and numerous stormwater ponds created in residential developments.

Rogerson said while stormwater ponds are useful to contain stormwater and provide some wildlife habitat, they do not mimic the functions of natural wetlands.

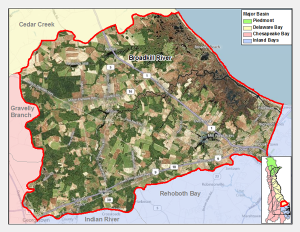

One of 16 watersheds that comprise the Delaware Bay and Estuary Basin, the Broadkill River watershed covers more than 68,000 acres in east central Sussex County. The watershed is primarily made up of agricultural land with some urban development and the 10,000-acre Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge.

The Broadkill River headwaters originate near the Town of Milton and flow 25 miles eastward toward Broadkill Beach into the Delaware Bay through Roosevelt Inlet in Lewes. Milton is in the center of the watershed, which stretches to outlying sections of Georgetown and Lewes, with Route 9 serving as the southern border. More than 23,000 people live in the watershed, which is about 10 percent of the county's population.

About 50 percent of the watershed is made up of farmland, 20 percent wetlands, 20 percent forest and 7 percent is considered urban development.