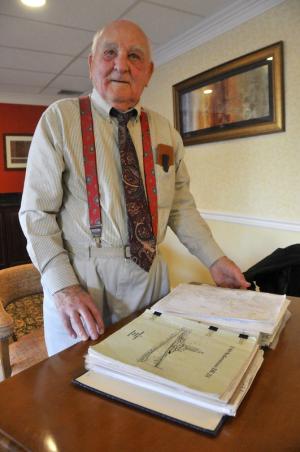

William Simpson: Navy veteran took part in four invasions

William Simpson knew the water. At least he thought he did, growing up in the waterfowl country of Talbot County in Trappe, Md.

He was 18 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Simpson did what millions of other young men did; he joined the military.

Assigned to the Naval destroyer escort USS Sederstrom DE-31, he would spend more than two years at sea – with little time on land – taking part in some of the most famous invasions in the Pacific Theater.

Now 90, Simpson lives with wife of more than 60 years, Helen, at Methodist Manor House in Seaford. He said he saw a lot of water, estimating that in two years at sea he logged more than 100,000 miles, criss-crossing the Equator at least 12 times, enduring seemingly endless rough seas and three typhoons.

He kept a meticulous record of his experiences during World War II and of his life after the war. He has been interviewed by two groups of students who recorded his memories.

He has a map of the Pacific, highlighting the places the Sederstrom went, places like the faraway Gilbert, Marshall and Mariana islands.

As he recalls memories from 70 years ago, Simpson says he wants to concentrate on the positive and not think about the negative. The negative would mean reflecting on a roll of honor showing the more than 100 destroyer escorts sunk during World War II and the thousands of lost sailors.

“There were a lot of boys out there who became men all of a sudden,” he says.

Simpson said he was fortunate. His ship weathered kamikaze attacks, and the Sederstrom survived the war with most of the same sailors who left Mare Island Naval Yard in California Sept. 11, 1943.

Aboard a unique ship

Simpson said his ship provided support to convoys during the invasions of Saipan, Guam, Okinawa and Iwo Jima. His ship also provided escort to merchant ships in the Pacific.

As a a third-class electrician's mate, Simpson worked below the main deck on the switchboard, an electrical panel that controlled the ship.

Because destroyer escorts were small, they could get close to shore. “I remember during the Saipan invasion, we had shells from our ships flying over our heads for two weeks, night and day,” he said. “We could see everything as it was happening.”

Five other destroyer escorts accompanied the convoy of 20 ships; Sederstrom was the flagship.

Destroyer escorts were unique ships that played a vital role in a convoy. They provided protection to submarines and could also attack enemy subs with depth charges. Because they could turn on a dime and do figure-eights at full speed, they were difficult targets for torpedoes and bombs.

Simpson said his ship was equipped with state-of-the art firepower with a range of 2,500 feet to provide cover fire for the larger and quicker destroyers. The ship was also equipped with the best sound detection equipment of the day.

Japanese kamikaze pilots never made a direct hit on his ship, Simpson said, but it's one of those negative experiences he would rather not expand on.

He said there was little down time aboard ship. When not at the switchboard, he stood watch or performed maintenance, and training was part of daily life on the ship. He said many hours were spent battle ready at general quarters.

“We were all young,” he said. “We had an excellent crew and officers that worked well together. We were a tight-knit group. That's the main reason we pulled through it, and we did a lot of praying.”

The 190 crew members grew so close they had reunions for many years. Simpson's small-world story involves one of his officers, Lt. Leonard Elgin. “I ran into him one day in 1950 on a street in Pittsburgh,” he said.

The final reunion took place in 2009; Simpson and one other shipmate attended.

Many stops at Pearl Harbor

Simpson still recalls how he felt when he heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor. “I was driving to work in a snow storm, and the news gave me cold chills,” he said. Little did he know that he would see Pearl Harbor several times within the next few years.

Simpson completed his basic training in Norfolk, Va., in 1942. He says he mostly remembers endless guard duty spent out in the cold.

He and his crew shipped out with no idea where they were headed and ended up in Pearl Harbor the first week of December in 1943, two years after the attack. “You could still see some of the damage, and the base was still on a 6 p.m. curfew,” he said.

Pearl Harbor would become the ship's base; the Sederstrom returned to Pearl four times during its two years of duty in the Pacific. The ship had a strong tie to the base: it was named for a sailor who died in the Dec. 7, 1941 attack.

Simpson said he had mixed emotions about returning to Pearl Harbor after the war. It took a long time, but he traveled there with his wife in 1985.

The war comes to an end

Near the end of the war in 1945, Simpson said he had a feeling they were preparing for an invasion of Japan. “If that had happened, I probably wouldn't be here today,” he said. “They wouldn't have given up.”

Dropping atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki was horrific, he said. It was also a relief, he added, because he knew that would mean an end to the war.

After the war, Simpson returned to the United States, eventually ending up in Newport, R.I., and Portsmouth, Va., where he was honorably discharged in 1946.

Unfortunately, his ship had a short lifespan. Simpson said repeated depth charge explosions had damaged the hull, and the Sederstrom was decommissioned and sold for scrap in 1947.

Vet has lived an active life

After the war, Simpson returned to his job as a telephone repairman specializing in security systems. He retired from Bell Atlantic after 43 years.

Retirement didn't slow him down. Simpson has participated in a variety of veterans and civic activities over the years. He even appeared as an extra in the movie “Runaway Bride” in his adopted hometown of Berlin, Md., where he lived from 1973 to 2005. He still has the stub from his $76 paycheck.

He also has been active in the American Legion, Lions Club, Boy Scouts and Telecom Pioneers, among other organizations. But he has always taken extra time to pay tribute to veterans and honor his country.

He and his wife have four sons, eight grandchildren and four great-grandchildren with a fifth due to be born in February. The couple lived in Millsboro before moving to the Manor House in 2011.

At the end of the war, 16 million veterans – called the Greatest Generation – returned home to family and friends. Today, 1 million World War II veterans are still alive. As Veterans Day 2014 approaches, William Simpson is proud to be among that number to assure that what he and his shipmates accomplished is not forgotten.