Aquaculture interests run deep, wide

Getting a lease for shellfish farming on state-owned subaqueous land is likely to be an expensive process.

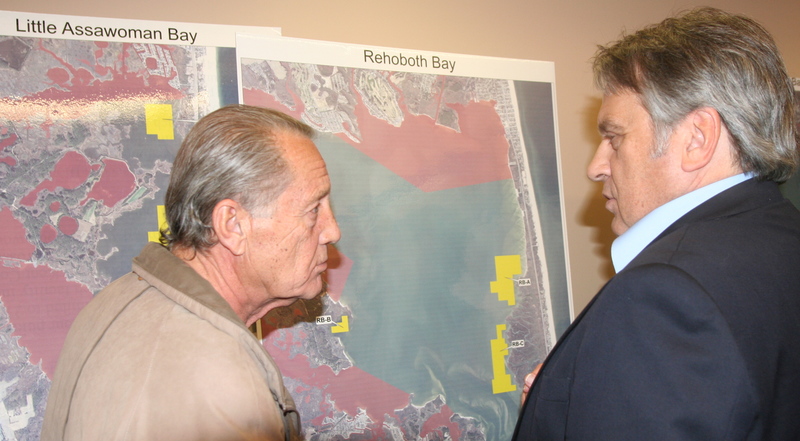

About 80 people attended a workshop last month to contribute to and learn about regulations being developed for growing oysters and clams in Delaware’s first aquaculture ventures.

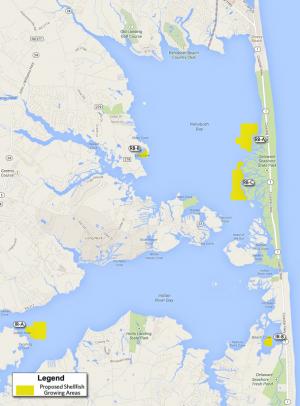

State officials offered more details about plans to allow cultivation of native Delaware species eastern oysters in Little Assawoman Bay, Indian River Bay and Rehoboth Bay, and hard clams in Little Assawoman Bay.

The state is aiming to have comprehensive regulations in place by July. Division of Fish & Wildlife officials are using workshops to gather public input about aquaculture and to educate the public about the industry.

A two-year process facilitated by the Center for the Inland Bays, resulted in recommendations used to establish state aquaculture law.

The areas are subject to change after additional feedback is received from various state and federal agencies.

Many questions remain, including who should survey aquatic parcels, how much it will cost and who should pay.

State officials said a marine survey team charges $4,000 to $5,000 – about $300 an hour – to survey one parcel. They said state-employed surveyors work only for specific divisions, DelDOT for example, and already have full schedules.

Officials said based on parcel disputes that have gone to court in other states, they’ve learned the first question judges ask is ‘Who did the survey?’ They said answers other than a professional marine surveyor typically lead to legal complications.

Oysters in the wild grow attached to a reef or to underwater objects – shells, rocks, large stones or pilings.

Farm-raised oysters are grown in a container. In the wild, clams live in underwater sediment, while in aquaculture, clams are raised in containers or are grown directly on the bottom.

State officials want those who are seriously interested in aquaculture to write a business plan containing concrete information such as the minimum number of shellfish seed they need to plant per year.

But many who said they might want to raise shellfish said they need estimated startup costs before they could decide.

Zina Hense, Division of Fish & Wildlife program manager, said start-up costs are not the only factor inherent in planning a shellfish farm.

“Some growers will invest time and effort buying materials to build their own cages. Other growers might choose to buy ready-made cages, making a substantial monetary investment,” Hense said.

“Growers also at times have the option of buying shellfish at different stages of maturity. Younger, smaller-size shellfish cost less but are riskier because smaller seeds require more care and are also prone to predation,” she said.

Hense said growers might also decide to invest in disease-resistant seed, or triploid seed to reduce mortality or reach market size faster. But officials said buying those advantages comes at a price.

Labor, too, can be a major expense for shellfish farms. Some growers will be able to provide their own labor, but others might need to hire help.

“There are many different ways to set up an aquaculture business, and these differences can result in a difference of tens of thousands of dollars in operating costs for businesses working the same amount of land,” Hense said.

The triploid oyster’s chromosomes differ from those of diploid regular oysters. Triploid oysters grow faster and larger than regular ones, and are also firmer and sweeter. But shellfish farmers pay premium prices for triploid seed.

State officials said they know starting a shellfish aquaculture business can be costly, but Division of Fish & Wildlife is committed to a successful shellfish program. They said they’re also committed to recognizing and protecting access to the bays for all bay users.

Recreational boater Dan Wien said there isn’t enough room in the three bays for aquaculture and recreational boating.

But DNREC officials disagree. They say under the new shellfish laws recreational bay users and the aquaculture industry can coexist.

“Without a doubt, the Inland Bays are densely populated, high-use areas. There is a need to carefully balance the existing uses with a shellfish aquaculture industry,” Hense said.

The next aquaculture public workshop is set for 6 p.m., Wednesday, Feb. 26 at DNREC’s Lewes Field Facility, 901 Pilottown Road, Lewes.

How much bay bottom will be farmed?

Proposed aquaculture development areas cover 140 acres in Indian River Bay, 322 acres in Rehoboth Bay, and 221 acres in Little Assawoman Bay.

Indian River Bay has a total of 9,941 acres, Rehoboth Bay’s total acreage is 9,913, and Little Assawoman Bay totals 2,521 acres.

Law limits the total acres of subaqueous land available for shellfish farming leases to no more than 5 percent of Indian River Bay and Rehoboth Bay, and no more than 10 percent of Little Assawoman Bay. Division of Fish & Wildlife officials are considering a lottery to determine who would receive the first leases.