Could Delaware Bay host future offshore wind port?

If you look east anywhere along the Delaware coast you won’t see it. But out there, above the waves and below the sky, a powerful force is constantly at work. It’s called offshore wind power, and with radically improving technology that power could become the northeast United States’ major source of electricity over the next 25 years.

The good news is it’s clean energy, it’s competing now with other traditional sources of electricity for lowest price, and the supply is practically unlimited. Some people don’t fancy the vision of offshore turbines whirling out along the horizon off Rehoboth Beach. But maybe the same high-minded people who have developed this 21st century technology can figure a way to color the turbines so they’re not as intrusive as some of the wind farms atop areas of the Appalachians.

That great offshore wind resource could eventually translate into a Delaware Bay port facility and lots of associated jobs up and down the bay, both for assembling and deployment of wind turbines, and for their operation and maintenance. I’ll get to that in a minute, but first ...

Some call the coastal waters off the East Coast the Saudi Arabia of wind energy. “This is a resource that doesn’t go away,” said Dr. Willett Kempton. A professor and researcher at University of Delaware, Kempton spends about half of his time on offshore wind power and the other on electric cars. “General Motors is shutting factories, so it will have a few billion dollars to spend on electrifying cars. Now that the technology is allowing offshore wind energy to be produced at a lower cost than grid electricity, the current price is equivalent to $1-a-gallon gasoline.”

Deepwater Wind, an offshore wind design-and-build company, recently completed the nation’s first and only operating offshore wind farm. Serving Block Island, off the coast of Rhode Island, that multi-turbine offshore installation is producing more than enough energy to power the island at less than half the cost that islanders paid previously.

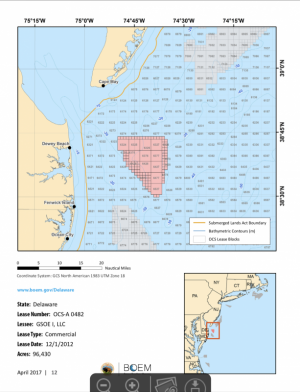

Danish firm Ørsted, the world’s largest offshore wind company, recently purchased Deepwater. According to Clint Plummer, vice president of Deepwater, Ørsted is keeping the Deepwater team in place that is working on the Skipjack wind farm being planned for the so-called Delaware Wind Energy Area off the coast of Delaware and Maryland. The nearest point of the Delaware Wind Energy Area is 13 miles from the Delaware beaches but Ørsted is not currently planning to site turbines that close to shore. Orsted's preliminary planning has turbines at least 17 miles from shore.

The Skipjack project encompasses only a small part of that federal wind energy area, which is out of shipping lanes and migratory bird flyways, and in water that’s not too deep. “The larger site,” said Plummer, “is a great area where lots of research is being done. We’re evaluating possible future development to serve the metro areas of Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey and D.C. But we need a customer to buy the energy if we build the size of installation Ørsted is capable of.”

Lauren Burm, head of public affairs for Ørsted, said the company has built farms in European waters capable of producing five gigawatts of power - enough to power 2 million U.S. homes.

At that scale, said Plummer, Ørsted, in heads-up price competition, can win on requests for proposals to supply power. “The metropolitan area of the country from Washington D.C. to Boston comprises about 5 percent of the nation’s land mass and 20 percent of the population,” said Plummer. “It’s also the nation’s oldest grid in terms of generating facilities, with an average age of 50 to 60 years. From a technology standpoint, that’s like comparing a Ford F150 back then to an F150 now. That’s why we can win. It will cost a lot to replace the aging facilities serving that densely populated area now.”

Kempton said a project off the coast of Massachusetts called Vineyard Wind - an 800-megawatt installation - is the only wind farm headed toward construction that is of the scale that Ørsted builds. Massachusetts state regulators, he said, are estimating $1.4 billion in savings to electrical customers over 25 years.

When Bluewater Wind was proposing a wind farm off Delaware several years ago, a subsidy from the state to Bluewater - via a tax on users in addition to their rate - would have been required to make the project financially viable.

“That’s not the case any more,” said Kempton. “What’s happening up in Massachusetts - with the estimated savings to ratepayers - is the opposite of a subsidy.”

Possible Delaware Bay port?

The scale of project that Ørsted and other developers envision for the mid-Atlantic area would probably require a new port facility. Kempton recently returned from a trip to Europe where he visited a number of offshore wind facilities, and ports and harbors being developed by cities and port operators specifically for the industry. In the U.S. water infrastructure legislation sponsored by Sen. Tom Carper that recently passed the Senate by a 99-1 vote, the Army Corps of Engineers has been given a year to study possible port and harbor sites in the country and analyze suitability of at least three possibilities.

Kempton, who does offshore wind work for an area much larger than just Delaware, said he sees no reason why at least one site shouldn’t be considered in Delaware Bay. “A real offshore wind port needs about 200 acres or more with a big flat area where wind turbines can be assembled and loaded onto ships for eventual offshore placement. They also need a channel of about 30 feet deep, and no bridges or overhead obstructions downstream. That’s why Delaware Bay makes so much sense. They’re not building these towers flat. They want them preassembled with everything inside, and then they put them together as an upright tower. They’re picked up by a crane and placed on a ship and taken out to sea when conditions are right. The towers are 300 feet tall from the ship deck up. Even the installation vessels themselves can require over 200 feet of overhead clearance. That’s why there can be no bridges or obstructions downstream,” said Kempton.

Delaware Bay has no bridges or obstructions below Delaware Memorial Bridge. Kempton said he knows of at least two sites - one on the Delaware side, another on the Jersey side - that could qualify. But he stopped at that.

It’s not difficult to envision those ships coming down the bay loaded with hundreds of turbines, and the jobs in the mid-Atlantic states that loading, assembling and supplying parts would entail. It’s also not difficult to envision the jobs that could come with crew boats and piloting operations out of Lewes.

“We’re already seeing jobs generated by offshore bottom geology and avian surveys, as well as design work,” said Kempton. “But that’s nothing compared to what’s coming.”

Editor’s Note: This column was corrected on Dec. 18, 2018 to indicate that Ørsted’s preliminary planning for a wind farm in the Delaware Wind Energy Area includes placement of turbines no closer than 17 miles from the Delaware coast.