Antoine Vann is preserving his family’s West Rehoboth legacy

Having grown up in Rehoboth Beach, and with family members all over eastern Sussex, Antoine Vann knew from an early age that his family had deep connections to the area. He knew his dad’s side was only a couple generations removed from when family member Elijah Burton donated land just outside Rehoboth’s town limits in 1881 to build a church for the Black community. He knew his mom’s side could trace their Nanticoke Indian heritage back even further.

“I’m about as local as local can be,” said Vann.

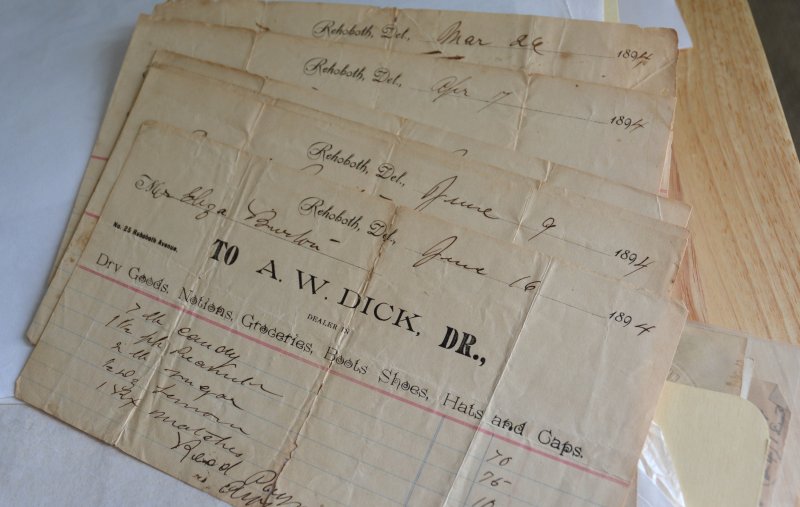

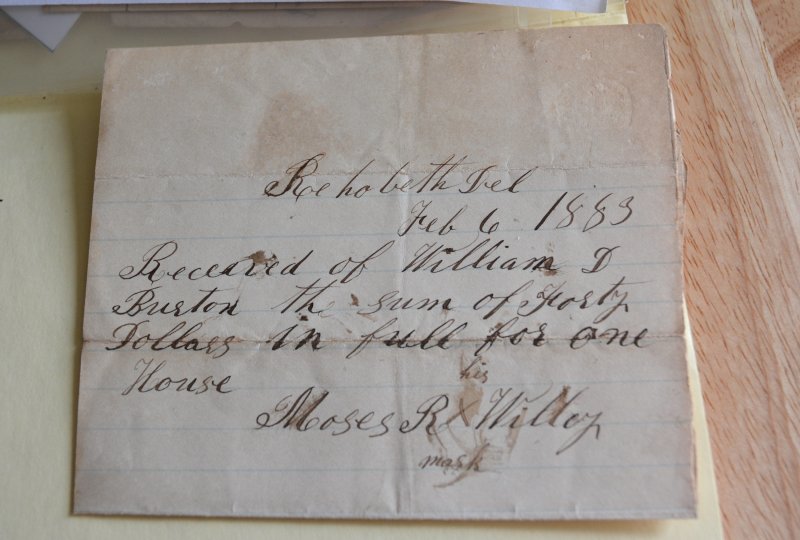

However, it wasn’t until the death of his grandparents on his dad’s side a little more than a decade ago that he was inspired to learn more and preserve his family’s history. He said he was helping clean out their house on Church Street when he found bags and bags of old receipts, postcards and pictures from over the years.

“We didn’t know it was there. They had kept everything,” said Vann. “All these things tell a story that I’m still trying to figure out for myself.”

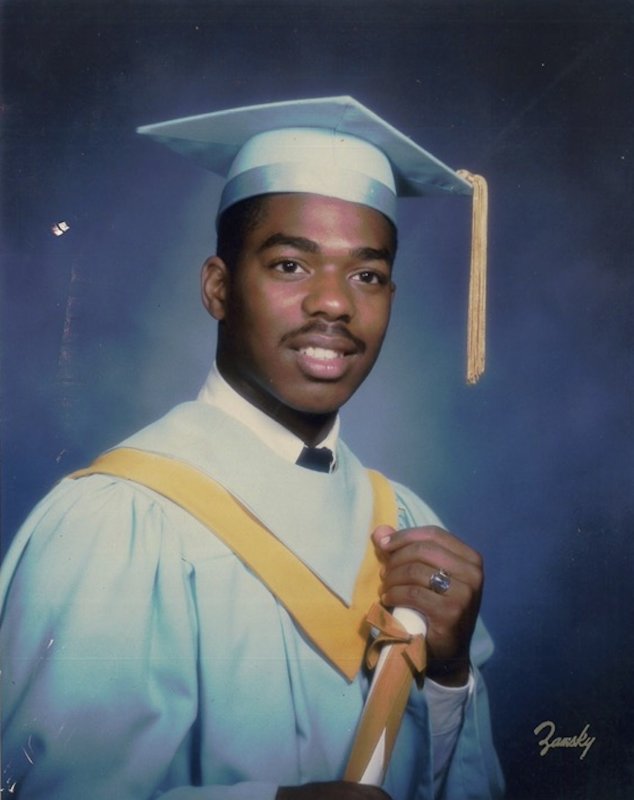

Vann graduated from Cape Henlopen High School in 1987. He spent almost all the formative years of his life in West Rehoboth.

Vann’s parents were teenagers when he was born – his mom was 17 and his dad was 18. They were in their early 20s when the family moved to Raleigh, N.C. Not long after making the move, his mother got cancer, and despite years of treatment, she died three years later, said Vann. As a result, his dad gave him the option of living with him in North Carolina or moving back to Rehoboth to live with his grandmother on his mom’s side.

It wasn’t an easy decision, but ultimately Vann decided to return to the support structure in Rehoboth.

“My dad was a Marine and didn’t play. Years later, he told me there was a lot of angst about the whole thing. I’ve thought about how my life would have been different if I had stayed in North Carolina, but this area was a great place for a kid to grow up,” said Vann. “I will say, I’m still a Tar Heels fan to this day.”

Vann said he kind of grew up in a bubble, where everyone knew who he was.

“I couldn’t be anonymous in these parts, but I knew I could get away with certain things. Everyone had known my mom. They knew my situation. I was somewhat rebellious,” said Vann, with a shrug of the shoulders and a smile.

Sitting in a room off to the side of the main living room of his grandmother Lucille Hood’s house, Vann said he grew up with his two uncles, one that’s five months older and one that’s younger. Originally, there were only four rooms in the house – the living room, kitchen and two bedrooms, he said.

The cottage sits at the end of a paved lane off Oyster House Road, between Burton Village and the Lewes-Rehoboth Canal. It’s one of a handful of cottages located in the immediate area.

“There used to be another one right over there,” said Vann, pointing to a grassy area next to his grandmother’s cottage.

“We grew up like brothers,” said Vann, of his two uncles. “My grandmother raised us by herself. She worked so hard.”

When Vann grew up, the area around his grandmother’s house hadn’t yet been residentially developed. There were industrial factories along the canal that no longer stand, there were woods surrounding and there were open fields, he said.

“This house used to be at the end of a dirt road,” he said.

Even to this day, Vann still goes out of his way to eat Sunday dinners with his grandmother, who is now in her 90s but still “sharp as tack.”

“I’ve made the drive from New York to be here. [And from] other different places,” said Vann. “I’ve always told her that if she’s having Sunday dinner, I’d be there.”

Vann said summers in Rehoboth were a great place for a kid to grow up. He can remember heading downtown with $2 to get a bag of chips and a soda, and still be able to go skating. It was also an open door for visitors.

“No matter where someone was from, they’d kick off their shoes, kick back and relax,” he said. “Someone would come and visit, have fun for a few days or weeks, and then they’d leave. Then someone else would come and visit, and we’d do it all over again.”

He can remember the days when Rehoboth basically shut down after Labor Day.

“Back then, a person could walk straight up Route 1 and not get hit by a car,” said Vann.

To visit friends or his dad’s side of the family on Church Street, he would walk out the back door and take a path that cut through to Rehoboth Avenue. He can remember when they built the concrete wall around apartments behind Henlopen Station. At first, there was a short wooden fence, but he and his friends would hop it. Then it got replaced with a slightly taller fence. Eventually, they put up that big brick wall, he said, laughing.

Vann’s son Terrance is the artist who painted the West Rehoboth Legacy Mural a few years ago.

“It was a full-circle moment,” said Vann, which is why he’s been a big supporter and organizer of the annual Juneteenth celebration that began at the same time.

In Vann’s lifetime, the number of family properties has gone from five to three. He said he doesn’t plan on selling any more, despite outside pressure to do so from unsolicited offers.

“Even if you’re not thinking about it, somebody else is,” said Vann, taking a page from his Nanticoke Indian ancestry’s principle of making decisions with seven generations of future family members in mind. “I hope my grandkids’ grandkids will still be able to come to Rehoboth.”

Chris Flood has been working for the Cape Gazette since early 2014. He currently covers Rehoboth Beach and Henlopen Acres, but has also covered Dewey Beach and the state government. He covers environmental stories, business stories and random stories on subjects he finds interesting, and he also writes a column called Choppin’ Wood that runs every other week. He’s a graduate of the University of Maine and the Landing School of Boat Building & Design.