The Cape Region’s other ocean outfall

Rehoboth Beach’s plan for an ocean outfall has raised persistent controversy over its effects on water quality.

But for Sussex County officials and those who work at the South Coastal Regional Wastewater Facility, ocean outfall has been a way of life since 1979.

Heather Sheridan has worked at the plant, located behind a group of residential developments a few miles off Route 1 in Bethany Beach, since it opened in 1976.

“The last thing I would want to do is pollute the ocean. We’re all very passionate about doing a good job. I think most operators are like that.”

Sheridan, the plant’s director of environmental services, not only works at the plant but also lives at a beach house not far from the discharge pipe passing between the Sea Colony high rises and Middlesex Beach, the area between Bethany and South Bethany. She said she frequently swims in the water there and that people would never know the outfall pipe is there unless they were told. The only other sign the outfall is there is the small pump station at the beach, which is checked weekly, Sheridan said.

She said critics of ocean outfall who approach the subject from an emotional standpoint, not a scientific one, frustrate her.

“Nothing that gets pumped out is going to end up on the beach,” Sheridan said.

Sheridan said the area where the pipe is, known as the diffuser site, has become a good spot for fishermen, who ask for the coordinates. She said fish like the warmer water and coral that has developed around the outfall.

District Manager Loran George said employees at the plant all enjoy the ocean. “They take a lot of pride in their work,” he said.

The pipe itself is mostly buried under the sand. Treated effluent is pumped from the facility through 11,000 feet of force main through a 30-inch pipe to the diffuser section more than a mile offshore. The diffuser section juts out of the bottom, Sheridan said, and into a Y shape, where the effluent filters out. The diffuser is similar to a sprinkler. Sheridan said divers inspect the diffuser every five years when the plant is repermitted.

The science behind ocean outfall

The proposed Rehoboth outfall is similar to South Coastal in that the pipe would go out 6,000 feet offshore, but with less piping required to pump the effluent to the disposal site off Deauville Beach.

Dr. William Ullman, professor at the University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean and Environment, said, “Rehoboth Bay is part of the ocean. It’s not like we’re changing where we’re dumping the stuff. The problem with Rehoboth Bay is it is a part of the ocean that is poorly flushed.”

He said the other problem is nutrients from the effluent in a poorly flushed water body can lead to algae blooms, which in turn can lead to fish kills. In the ocean, the water body is deeper and dilutes nutrients much faster than the Inland Bays do, Ullman said.

“We’re not changing very much. We’re moving the pipe from a place where it is poorly situated to a place where it is better situated,” he said. “We already have an ocean outfall. We’re just moving it to a better place.”

Upgrades to Rehoboth’s treatment plant have dramatically reduced its phosphorus and nitrogen loads that will reach the ocean, Ullman said. Phosphorus and nitrogen promote plant growth, which cuts down the oxygen in the water available for fish, he said. Besides South Coastal, Ullman said, Ocean City,Md. also has an ocean outfall.

Ullman said ocean outfall was the most competitive option for Rehoboth's wastewater as far as cost and practicality.

“I think for all points of view: technical, environmental and financial, it seems to be the best choice for Rehoboth,” he said.

Any problems with bacteria on the beach, Ullman said, are more related to stormwater than to wastewater. In his decision allowing Rehoboth to seek $35 million for the outfall and plant upgrades, Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control Secretary David Small mandated the city study improvements to its stormwater system and complete the study by Jan. 1.

“There’s no bacteria left in wastewater. Wastewater is sterilized; it’s filtered before it goes back out into the environment. Wastewater is highly treated. Stormwater is untreated, for the most part,” Ullman said.

One concern brought up by opponents of the Rehoboth outfall is pharmaceuticals getting into the water, but County Engineer Mike Izzo said that is not a problem because there are no industrial users flushing water that would contain a lot of metals. The only way for pharmaceuticals to get into the wastewater system is by people flushing their pills down the toilet.

South Coastal is equipped to handle far more capacity than Rehoboth, up to 9 million gallons per day, as opposed to Rehoboth, which will be upgraded to treat 3.4 million gallons per day. South Coastal’s peak effluent flow is 4.5 million gallons per day in the summer, whereas Rehoboth’s peak is about 1.5 million gallons per day.

South Coastal also treats a larger area, including Bethany, South Bethany, Fenwick Island, Ocean View, Millville and as far west as Selbyville. Izzo said South Coastal is built to accommodate new development west of Bethany. Rehoboth will treat its own wastewater plus Dewey Beach, North Shores and Henlopen Acres, whose sewer is handled by the county but treated in Rehoboth. Sussex County is a 40 percent partner in the Rehoboth outfall project.

Outfall vs. land application

South Coastal is one of four plants operated by Sussex County, and the only ocean outfall. The county’s three other treatment plants – Inland Bays, Piney Neck and Wolfe Neck – were built in the early 1990s and use land application. Izzo says the reason for this is twofold: for one, they were built after the state mandated all effluent discharge out of the Inland Bays and second because these facilities are farther inland, making it to expensive to pump the effluent to the ocean.

“Here, where we’re adjacent to the ocean, this is the solution that makes sense. Picking up Rehoboth’s flow and moving it 10 miles inland makes no sense. We have a high groundwater table. Plenty of groundwater supply. There’s not one area of Sussex County where we have a concern about available groundwater,” Izzo said.

Ullman echoed that sentiment.

“I have no problem with spray irrigation. I just don’t think it’s a good technical solution or a good financial solution for Rehoboth,” he said.

Ullman said spray irrigation would be worse for critics concerned about pharmacueticals, since those pharmaceuticals would be going into the groundwater.

Sheridan said it was interesting that people want more spray irrigation; she recalled when the county built the spray plants 20 years ago, people thought toilet paper was going to be hanging from the trees.

A look around South Coastal

The South Coastal plant serves as the nerve center of all the county’s sewer operations. Computers can monitor all the 400-plus wastewater pump stations throughout the county.

“You really never leave your job,” George said.

Raw sewage enters the plant at the headworks.

“This is the stinkiest part of the plant,” Sheridan said.

The solids are screened to filter out trash and other waste.

“It’s shocking what people can get down the toilet,” Sheridan quipped. “Beach towels? How do you get a beach towel down the john?”

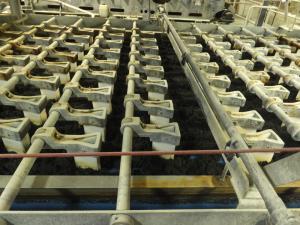

After the incoming sewage is screened, it is pumped to a clarifier, where it slowly turns into a brown mix of water and solids. George called this “mixed liquor,” and it has an earthy, dirt-like smell. Further treatment removes the solids; the treated water that will eventually go out to the ocean is clear enough to resemble drinking water.

George said there’s no precise time for a gallon of water to go in and a gallon to go out. Variables include how much solids are in the system and what the flow is, he said. The plant itself is located on 54 acres, with an extra 10 acres serving as a buffer between the plant and the surrounding area.

The solids from the treated wastewater continue to be processed, as the water is squeezed out, leaving a dark-colored, cake-like product. Once the cake is dry, it goes into an oven where it is heated at 157 degrees for 30 minutes. Finally, the cake is mixed with lime and turned into fertilizer for farmers. The lime kills pathogens and dries out the sludge.

Failure has never been an issue at the plant, which has extra storage basins and backup generators to account for any problems. Izzo said flooding of the stormwater system is a bigger problem than anything at the plant, which is built to withstand storms.

“We’re quite proud of our place,” Sheridan said.

Ryan Mavity covers Milton and the court system. He is married to Rachel Swick Mavity and has two kids, Alex and Jane. Ryan started with the Cape Gazette all the way back in February 2007, previously covering the City of Rehoboth Beach. A native of Easton, Md. and graduate of Towson University, Ryan enjoys watching the Baltimore Ravens, Washington Capitals and Baltimore Orioles in his spare time.