Citizens oppose Artesian, Allen Harim permits

Operating permits to treat and dispose of wastewater from Allen Harim’s Harbeson poultry plant drew sharp opposition from area residents at an Aug. 21 public hearing.

Citizens packed the cafeteria at Mariner Middle School in Milton to give comment on two permits: one for Allen Harim to treat up to 4 million gallons of wastewater per day at the Harbeson plant, including wastewater from Allen Harim’s Millsboro and Dagsboro facilities.

The second permit would allow Artesian to accept the treated effluent from Allen Harim via an 8-mile pipeline and dispose of the effluent at the Artesian Northern Sussex Regional Reclamation Facility, soon to be renamed as the Sussex Regional Recharge Facility. Artesian would be allowed to spray irrigate crop fields with an average daily flow of 1.5 million gallons and a peak flow of 2 million gallons per day. The 1,700-acre site, which begins at the intersection of Route 16 and Route 30, also includes a 90-million-gallon lagoon for storage of treated effluent.

The main concerns of citizens were the level of treatment of the wastewater, groundwater pollution and the application process. Speakers also complained that they were allowed only three minutes to speak on two applications while representatives from Artesian were allowed to give a 10 minute presentation.

Tom Didrio, of Milton, said “We as citizens have very little faith in a system that has shown itself to be a protector of big corporate interests, who have been poisoning Delaware’s water for years, at the expense of the health and welfare of its citizens.”

He cited Allen Harim’s past history of environmental violations and drinking water contamination related to Mountaire’s Millsboro plant as reasons for his opposition.

Keith Steck, of Milton, asked what happens if Artesian’s lagoon gets full. He also said there is no documentation of contingency plans in case of a system failure.

Derrick Caruthers, of Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s groundwater discharge division, said the Allen Harim plant has checks in place to ensure that effluent that leaves the plant is safe for the environment. He said the permit includes monitoring provisions specifying testing frequency. When the wastewater is treated, it will also be tested, Caruthers said, and anything less than safe would be diverted back for retreatment.

Citizens, however, remained skeptical.

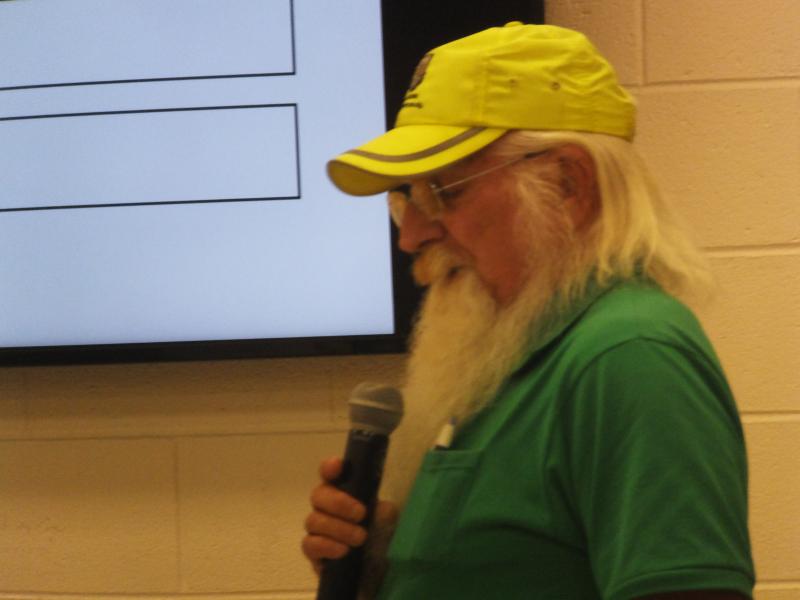

Ken Haynes of Millsboro said residents were promised that Allen Harim was going to build a state-of-the-art wastewater treatment system, but those promises were not kept. He then lifted his pant legs to mock wading into nonexistent water.

Ken’s wife, Joanne, said of Allen Harim, “We haven’t been happy with you at all. In any of your decisions. We’ve been told we complain too much, but we live right there. This is wrong. Start worrying about the people.”

On the Artesian side, Daniel Kostanski, Artesian’s project engineer, said Allen Harim spent $30 million in 2016 to upgrade its plant and that there is continuous and direct monitoring of the company’s wastewater. He said once the flow reaches Artesian, there is additional monitoring before spraying occurs.

Kostanski said if there is a problem with the effluent, spraying can be ceased or spread out over a wider area, and the lagoon will always have excess capacity available. He said Artesian also has the ability to do some treatment on-site.

“This is an actively managed facility, making sure that we are constantly adjusting for real-world conditions in the fields,” Kostanski said.

While Artesian and Allen Harim painted a rosy picture of the operation, those in attendance still raised concerns.

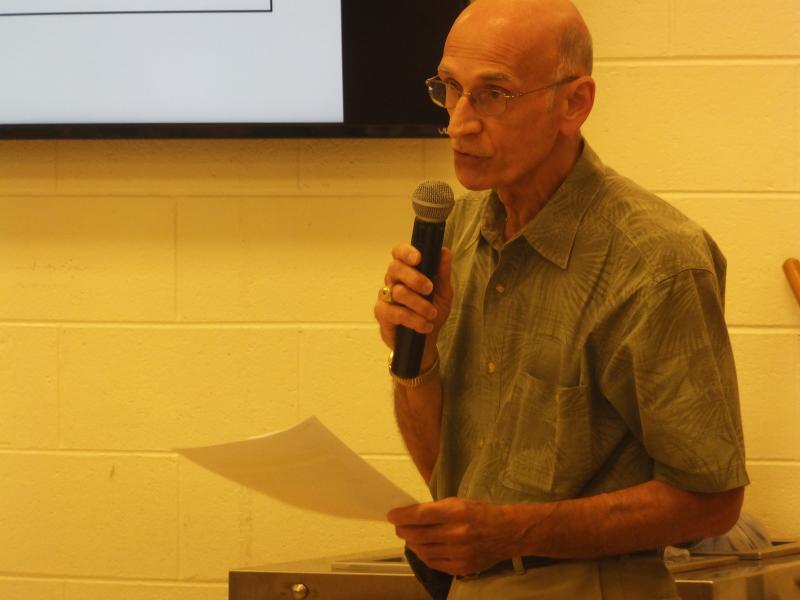

Anthony Scarpa, of citizens group Keep Our Wells Clean, said the application for Artesian’s permit is incomplete because there is no data for residential well testing within 1 mile of the facility. He said the Artesian fields are adjacent to fields owned by Clean Delaware that have a history of contaminating drinking water.

“If Artesian and DNREC are truly interested in protecting public health, and not just in a cheap way to assist the poultry industry in disposing of their wastewater, then this application should be suspended until extensive well testing and public health evaluations are completed,” Scarpa said.

Andrea Green, also of Keep Our Wells Clean, said Artesian’s proposal is inconsistent with its conditional use as granted by Sussex County, and the conditional use itself was based on findings of fact that are no longer applicable. The Artesian site was originally going to be used for a development called Elizabethtown, but when plans for the development fell through, Artesian searched for partners until an agreement was struck with Allen Harim in 2017.

Following the meeting, Green said, “The engineer last night, and Artesian in its massive public relations campaign, presented this as if it’s the great solution to the wastewater problem. Too many people immediately say that removing point source pollution - wastewater going into a body of water - makes this a great project. I struggle to see the ‘win’ for the aquifer and the people in Sussex County who depend on wells for drinking water.”

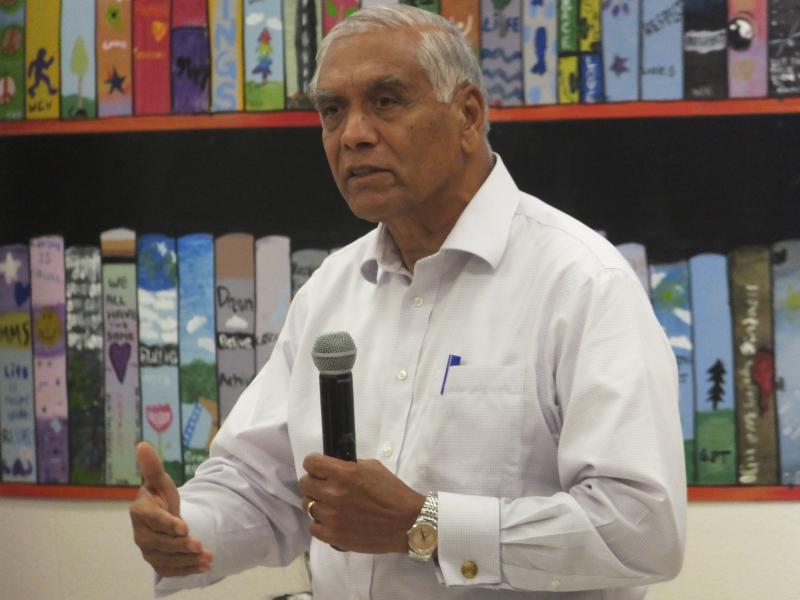

Dr. Mohammad Akhter of Selbyville said no public health study has been done on the project. He said the areas around the chicken plants, specifically Dagsboro and around Millsboro, have high rates of cancer and heart disease related to polluted drinking water. Akhter said Allen Harim and Artesian are applying 19th century solutions to a 21st century problem.

“We want solutions that will enhance the industry. We love the industry, the poultry industry, they should prosper, but also protect the health of our people,” he said.

Hearing officer Lisa Vest said the record will remain open through Friday, Sept. 20. No decision will be made until all public comment is received and reviewed.

Comments can be submitted at https://dnrec.alpha.delaware.gov under public hearings, or by mail to Lisa Vest, Hearing Officer, Office of the Secretary, DNREC, 89 Kings Highway, Dover, DE 19901.

Ryan Mavity covers Milton and the court system. He is married to Rachel Swick Mavity and has two kids, Alex and Jane. Ryan started with the Cape Gazette all the way back in February 2007, previously covering the City of Rehoboth Beach. A native of Easton, Md. and graduate of Towson University, Ryan enjoys watching the Baltimore Ravens, Washington Capitals and Baltimore Orioles in his spare time.