Fort Miles isn’t all World War II

Editor’s note: This is the second part of a series about history hiding in plain sight at Cape Henlopen State Park. The first part focused on the park’s role during World War II. It can be found at https://tinyurl.com/pm7k8m64.

While much of today’s focus at Fort Miles is on the World War II era, Cape Henlopen State Park’s strategic location has made it an important piece of land for centuries.

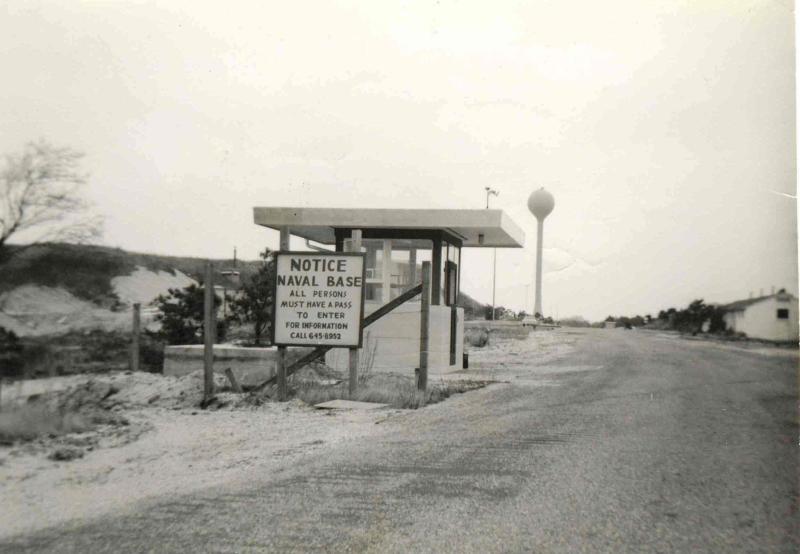

The southern side of the Lewes end of the park is where most of the activity occurred after World War II. The recently renovated Biden Environmental Center was built in the 1960s as Naval Facility Lewes, which used was for top-secret sonar to spy on Soviet submarines during the Cold War. By the early 1980s, the building was turned into a Naval Reserve facility until it was ultimately acquired by the State of Delaware with the help of then-Sen. Joe Biden in 1996.

“We were the site of most major continental defense during the Cold War,” said Kaitlyn Dykes, interpretive program manager with the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. “We’re part of what they call National Emergency Command Post Afloat, which was a program to rescue the president in case of nuclear attack. We were a satellite location for that.”

According to Christopher Bright, a Cold War scholar and professional lecturer at George Washington University, Fort Miles was used to communicate with the USS Wright and USS Northampton, two special ships that could be used as a floating White House in case of emergency. Bright said the U.S. worried about a surprise attack similar to Pearl Harbor, but the Soviet Union’s nuclear capabilities made it even more concerning. He said plans were developed to allow the president to leave Washington in a hurry and take refuge elsewhere. One of those sites was off the East Coast. Photographs from the Cold War era show large antennae atop Battery 519. The Fort Miles Historical Association says those antennae were used for National Emergency Command Post Afloat.

Pointing to the book “Raven Rock” by Garrett Graff, Bright said either the USS Wright or the USS Northampton was always at sea, alternating every two weeks. Per the book, the vessels cruised aimlessly off the Atlantic Coast and were a quick helicopter ride away from Washington. The book also says Cape Henlopen was the primary communications node, with backup facilities in Massachusetts and North Carolina.

Battery Smith behind the Biden Center is the largest underground building for Fort Miles at about 600 feet long. It was built before Battery 519, now the site of the Fort Miles museum. Battery Smith was built for two 16-inch guns, which are the largest guns ever housed in Lewes. It was used as an auxiliary building when Navy arrived.

DNREC Division of Parks and Recreation Operations Section Administrator Grant Melville said a movie screen and basketball hoop are still inside the facility. There was also a barbershop inside, and it was used as a motor pool and for storage.

Across the road in the primitive camping area sits another underground structure. This was the plotting room for Battery Smith, but it was later turned into a club for the Navy, and it even had a bar inside.

“With the help of the Fort Miles Historical Association’s Bunker Busters and the Coastal Defense Group, we’ve gotten these buttoned up,” Melville said.

He said it wasn’t until five years ago that the park had all areas secured. Until then, he said, there would occasionally be some people snooping around.

Battery Hunter, the site of the Hawk Watch, was repurposed during the Cold War. Today, MIUW is still painted on the entrance adjacent to the stairs up to the Hawk Watch. It stood for Mobile Inshore Undersea Warfare Unit, a group responsible for spying on Soviet submarines. Fort Miles was also part of the U.S. Sound Surveillance System, which had a similar mission.

“During the Cold War, the prospect arose that a foe – Soviet Union – might approach with submarines that would be equipped with nuclear missiles that could be fired to U.S. cities or nuclear weapons bases in the U.S.,” Bright said. “Fort Miles existed to protect ships. Now it had a similar role to protect against submarines offshore.”

To accomplish this, the Navy placed what amounts to microphones in the water off the coast to monitor activity. Bright said if would indicate if Soviet submarines were out there, and the military could track their rotations and positions.

“At the time, this was a very confidential project,” he said. “The U.S. didn’t want the foe to understand the capabilities of detection and tracking. That was significant activity that contributed to global stability and U.S. security at the time.”

The military was also monitoring the air for enemy aircraft. A photograph from the time shows a radar dish atop Tower 12, which is located next to today’s campground. Part of the Missile Master Program, the radar dish was first tested at the tower before being moved to Battery 519.

Bright said there was concern in the early part of the Cold War that the Soviets might launch a bomber attack. The U.S. developed an elaborate system to warn about the potential approach of enemy bombers and defend against those planes when they arrived. Bright said the military also had missiles and guns around cities, including Wilmington and Philly, and if enemy aircraft got close enough to those populated areas, the missiles could be used to shoot them down if U.S. aircraft had not done so already.

“This required an elaborate radar system to track bombers and help track missiles that were fired,” Bright said.

At Herring Point, south of the Biden Center, Battery Herring sits just beyond the parking area overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

“There is definitely a lot of interpretive potential with Herring,” Dykes said. “It’s the site of most of the Cold War testing. I think there’s a lot we could talk about at Herring, but of course like any of our other bunkers, first we need to make sure that it’s safe.”

Melville said there are no utilities running to Battery Herring. The park recently ran a water line to the lower parking lot nearby for a shower, but the line would have to be extended to Herring, and electric would have to be run, too.

“[Battery Herring] is a really cool story no one really knows about,” Melville said. “During the Cold War, we were more prominent in coastal defense than we were during World War II.”

In addition to the top-secret sonar project, Fort Miles was also a location for the Bumblebee rocket project and the Nike missile project. Bumblebee rockets were the first U.S. weapons to use ramjets, a powerful engine that works by sucking in air and converting it to fuel. The Nike project delivered the U.S.'s first operational anti-aircraft missile system

Fort Miles started giving up pieces in the 1960s to become Cape Henlopen State Park. The first sections were in the northern part of the park, which explains why the area around the Biden Center and Battery Herring have much more Cold War history.

Pre-Fort Miles

Due to its strategic location, Cape Henlopen has been the site of military activity since its discovery. It was used during the Revolutionary War, the Spanish-American War, both World Wars and into the Cold War.

In the fishing pier area near the pavilion is the foundation of a brick structure that was the surgeon’s house, part of the Breakwater Quarantine Station long before Fort Miles existed.

“In the late 1800s, this was all a quarantine station,” Dykes said. “If you wanted to get into Philadelphia, just like Ellis Island in New York, you had to stop here and make sure there wasn’t illness on board before you could go up to Philadelphia.”

Most of what was the quarantine station is gone, but the foundation of the surgeon’s house remains.

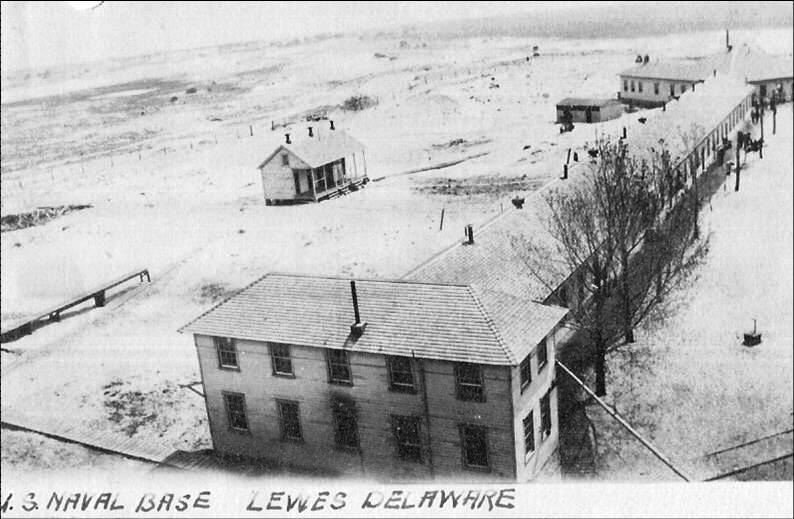

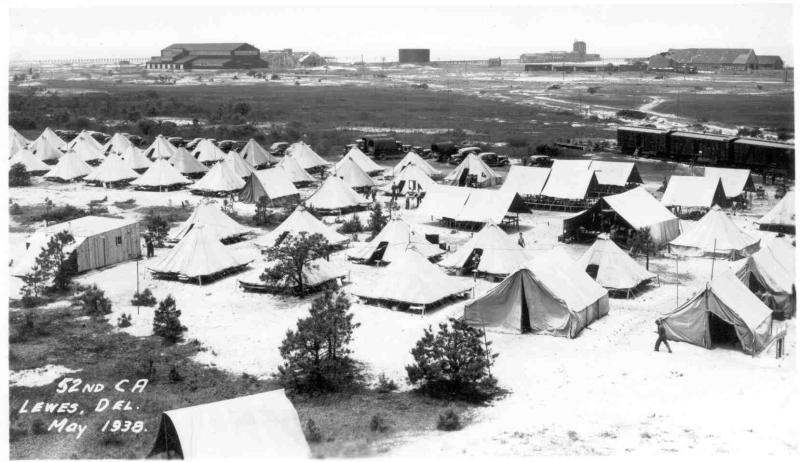

The quarantine station was repurposed during World War I. Dykes said there are photographs of Navy sailors sleeping in the old quarantine station. During World War I, a naval section base operated near what is now the Point.

The Army used Cape Henlopen for training long before the establishment of Fort Miles. In a 2012 feature in the Delaware Wave, Horace Knowles reminisced about the establishment of a permanent base when he served in the 261st Coast Artillery with the National Guard. He said at the tail end of a three-day training session in 1941, his captain gave orders to stay and help build a fort to protect the Delaware River and Bay. He said it was initially known as Camp Cranberry among the crew there, but was changed to Camp Henlopen a few weeks later.

Dykes said in addition to the programs and events at Fort Miles, DNREC has programs about the Cold War. She’s also working on a program about the quarantine station she hopes to roll out before Delaware’s 250th anniversary celebration in 2026. The goal is to talk about what coming to this country was like for different generations.

Also, Dykes hosts a trucking through history program where participants are driven around the park in a historic CCKW military truck while they learn about the area’s history. The program is likely to return in the fall. Additionally, history hikes are often held in the spring and summer.

To learn more about programs at Cape Henlopen State Park, go to destateparks.com/programs.

Nick Roth is the news editor. He has been with the Cape Gazette since 2012, previously covering town beats in Milton and Lewes. In addition to serving on the editorial board and handling page layout, Nick is responsible for the weekly Delaware History in Photographs feature and enjoys writing stories about the Cape Region’s history. Prior to the Cape Gazette, Nick worked for the Delmarva Media Group, including the Delaware Wave, Delaware Coast Press and Salisbury Daily Times. He also contributed to The News Journal. Originally from Boyertown, Pa., Nick attended Shippensburg University in central Pennsylvania, graduating in 2007 with a bachelor’s degree in journalism. He’s won several MDDC awards during his career for both writing and photography. In his free time, he enjoys golfing, going to the beach with his family and cheering for Philadelphia sports teams.