Lewes-based team first to witness deep-sea volcano impact

Andrew Wozniak started his day April 29 with a light breakfast – toast, no coffee.

The associate professor of chemical oceanography at the University of Delaware’s School of Marine Science and Policy in Lewes was about to climb into a mini submarine, called the Alvin, and dive almost two miles down to the floor of the Pacific Ocean.

It was an eight-hour round trip on the cold, cramped, titanium sphere with no bathroom onboard. But, what he and a colleague saw that day changed the course of science.

They were the first to witness the immediate impact of an undersea volcanic eruption.

“No one has gotten this close to something so fresh,” he said. “We were there and saw it the day before and the day after.”

“They were thinking it happened five to eight hours before they got there,” said Sunita Shah Walter, an associate professor and experienced deep-sea organic geochemist from the Lewes campus, who was also on the trip.

Wozniak, Walter and the six other University of Delaware researchers just returned from the month-long expedition. They sailed 1,200 miles west of Costa Rica to an area called the East Pacific Rise.

It’s a region that has been studied for decades, because of its undersea volcanic activity.

“The goal of the mission was to study the chemistry of higher thermal vent ecosystems,” Wozniak said. “They’re fascinating places to study for biological, chemistry and geological reasons.”

Their specific target was a vent named Tica, which is a Costa Rican term for a woman. Another University of Delaware professor gave it that name years ago.

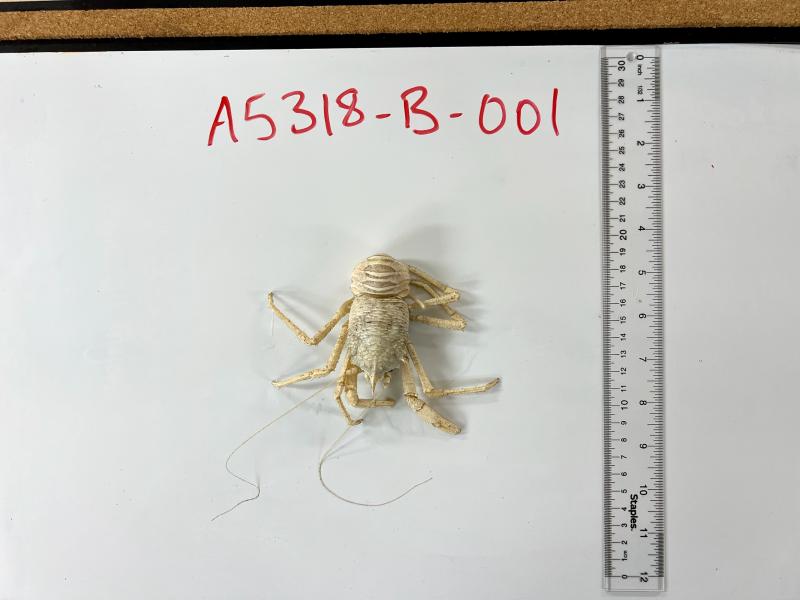

The day before Wozniak’s historic dive, video showed a thriving habitat of deep-sea creatures – tube worms, mussels, squat lobsters – in clear water. But after the eruption, it was a much different scene.

“It had been paved over, like blacktop,” Wozniak said. “It’s smokier, there are particles everywhere. We thought, ‘This is odd.’”

“It was black basalt rock that shimmered like diamonds and pearls. It was one of the most stunning things I’ve ever seen,” Walter said.

While they did not see the actual eruption, Wozniak said they did witness flashes of light. They saw it all from the windows of the Alvin, the mini sub owned by the U.S. Navy. It is packed with switches, lights and monitors inside, and a lot of gear outside.

“There’s a big basket in the front that holds all of the sampling equipment and two [robotic] arms that take samples and put sensors in places,” Walter said.

Wozniak said the light fades away as the Alvin descends into the depths.

“It’s less driving and more floating,” he said.

Walter’s husband is a former Alvin pilot and the new director of marine operations at the Lewes campus.

Wozniak said when Alvin got down to the sea floor, they knew the area was unstable because the water temperatures were steadily rising. But, he said, they never felt like they were in danger.

He said their observations forced them to change the entire purpose of their mission from exploration to documenting the immediate aftermath.

Wozniak said rock and biological samples are being shipped back to Lewes. When they arrive, they have a lot of lab chemistry ahead of them.

“We have water and filters that we will use to examine them for various organic matter and compounds,” he said. “Sunita’s group does a lot of radiocarbon dating that can tell us the source of where it’s coming from.”

Some of the samples will be going to other universities and research organizations.

Wozniak said his trip was made possible by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

He said he hopes to go back to Tica one day, but he admits it will take another grant and a lot of planning.

Walter is heading out on another ship to study canyons in the Continental Shelf just offshore from Ocean City, Md.

They said the research is all connected to the big picture of understanding life on Earth.

“If we want to understand how to interact with the ocean, in terms of utilizing resources, understanding fisheries, all these things, we have to understand the chemistry,” Walter said. “Iron gets from the hydrothermal vents, across the oceans and serves as a fertilizer for phytoplankton, which is the base for food for everything from phytoplankton to tuna. What is the connection between the material coming out of the vents? How does it support ecosystems?”

.jpg)

Bill Shull has been covering Lewes for the Cape Gazette since 2023. He comes to the world of print journalism after 40 years in TV news. Bill has worked in his hometown of Philadelphia, as well as Atlanta and Washington, D.C. He came to Lewes in 2014 to help launch WRDE-TV. Bill served as WRDE’s news director for more than eight years, working in Lewes and Milton. He is a 1986 graduate of Penn State University. Bill is an avid aviation and wildlife photographer, and a big Penn State football, Eagles, Phillies and PGA Tour golf fan. Bill, his wife Jill and their rescue cat, Lucky, live in Rehoboth Beach.

.jpg)

.jpg)