There were once as many as 2,500 people working at Fort Miles.

Now, Lydia Wagamon is among the last surviving military and civilians who served at the fort during World War II from 1941 to 1945, in what is now Cape Henlopen State Park.

Lydia recalls her years at Fort Miles like it was yesterday. The sprawling 5,000-acre fort was built to defend against attacks by German ships.

“Those were special times,” she says with an infectious smile. “I lived a lifetime in those four years at Fort Miles.”

Dressed in red, white and blue, Lydia returned recently to the fort's museum in Battery 519. Her face lit up as she recalled long-gone days.

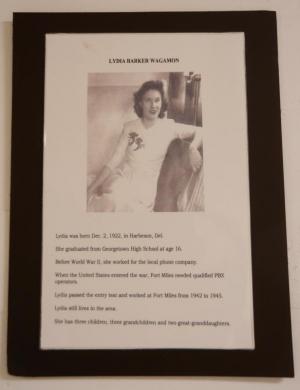

The 94-year-old, who was born and lived for 92 years in her family home in Harbeson, now lives at Brandywine Living at Seaside Pointe in Rehoboth Beach.

After graduation from Georgetown High School in 1940, Lydia got a job as a telephone operator in Georgetown.

But on Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked, and the lives of everyone changed . “Everyone was shocked. I had two classmates who went down on a ship, which was hard. It was a very, very emotional time,” she said.

When war broke out, she made up her mind to work at Fort Miles. Because of her experience, she was hired the day after she applied.

She worked in a bunker at Fort Miles, operating a switchboard with a team of other women, relaying messages from all over the world to locations within the fort.

She said she constantly had to correct the pronunciation of the location of the fort. “I made sure they knew it was Lewes and not Lous,” she said.

“I slept here, ate here and worked here because we had shift work,” she said. “We handled important calls from overseas during that terrible war. It made you shiver at times to think those wires could carry that.”

In the communications bunker, the switchboard room was across from the radio room. Lydia said security was strict around the bunker. “We had to use a signal outside so those inside would know it was you,” she said. “Then they would open the big steel door to let you in.”

She said everyone who worked in the bunker was aware that because of the importance of communications, their bunker would be targeted by the enemy if an attack ever took place.

Lydia says she didn't worry about it. “Hitler knew we had stronger forces than Germany did,” she said, still confident and proud of the work she did.

And she never talked about her job once she left the fort. “You didn't carry it with you anywhere else,” she said.

Lydia also recalls the social life at the fort, especially USO dances. “We had so many well-known bands,” she said. “The buses would go from town to town getting girls to the fort who wanted to dance.”

She said soldiers spent their leisure time playing baseball and football, and boxing.

She was a member of the Gray Ladies of World War II, trained through the Red Cross to respond to emergencies. “I was helping my country out. I wasn't a WAC, but I was doing a WAC's job,” she said.

Lydia says every time she comes to Fort Miles, she passes the bunker where she worked 75 years ago. “I'd love to go back inside and see it,” she says.

Childhood days at the beach

Before it was Fort Miles, the area was a favorite beach for people in the area. Lydia said she spent many hours during her childhood there. “If you didn't have a beautiful tan by May 1, it was terrible,” she said with a laugh.

She said a favorite tradition was to go to the beach on Easter Monday and roll down the sand hills with Easter eggs. “We had it made. We really were the greatest generation,” she said.

But that came to an abrupt halt in the 1940s. The beach was closed, and construction at Fort Miles began before Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Once construction was completed, Fort Miles became a small city as one of the most fortified locations on the East Coast.

German prisoners housed in the area

Few people realize that German prisoners were housed throughout Sussex County. The last two years of her service, Lydia worked at the Fort Miles Station Hospital, which was off base near what is now the Sussex Consortium. There she met German POWs who did odd jobs, and cleaned the hospital and grounds. “They liked it here, and they were sorry when they had to go back to Germany,” she said. “They didn't want the war any more than we did.”

One of the prisoners did a painting for her, which became one of her most cherished possessions, and it still hangs in her home today.

It's a painting of two ships Lydia saw in a Life Magazine photograph hanging in President Franklin Roosevelt's office. “I got the supplies for him, and he actually ended up painting another smaller painting for a friend of mine who was a nurse,” she said.

Over time, Lydia has forgotten the painter's name. “Those prisoners could do anything.”

When the war ended, Lydia wound up with the hospital's two mascot cats, Jack and Jill, and also sections of a fence the prisoners had built, which she placed around her flower garden at home.

As many as 3,000 German and Italian POWs were housed at Fort DuPont in Delaware City from June 1942 to June 1946. The POWs were sent to camps throughout the state including camps at Fort Miles, Lewes, Georgetown, Bethany Beach and Bridgeville. Prisoners did farm and factory labor, and helped build the Rehoboth Beach Boardwalk. Some helped build some of the first chicken houses in the county.

Up to 1,000 POWs were housed at Fort Saulsbury in Slaughter Beach.

Life continues after the war

After the war, Lydia married Richard Wagamon of Milton, who passed away in 2000. She has three children - Brenda Hughes, Kristie O'Donnell and Richie Wagamon; three grandchildren - DJ Hughes, Hannah Wagamon and Daniel O'Connell; and two great-grandchildren - Lelia and Daisy Hughes.

She raised her children and had various jobs, including working for Diamond State Telephone and selling Avon for 49 years. She has won more than 20 Presidential Awards for her sales.

The family has deep roots in the Milton area. The first Wagamon mill dates back to 1901; it was owned by William Wagamon and John Hamilton. That four-story mill was destroyed by fire in 1943 and replaced with the Diamond State Roller Mills plant, which was closed in 1958. The property fell into ruin and was eventually brought down in 1972 by a controlled burn.

After the family mill closed, her husband worked for Mutual of Omaha. As result of his business, the couple won trips and traveled all over the United States and Europe.

Lydia has recently suffered through tough medical times. Her daughter, Brenda Hughes, said it was touch-and-go in 2015 as complications from congestive heart failure started to break her down. A valve transplant literally saved her life, and she has staged a remarkable comeback.

Her daughter says that's not the only time she has beaten the odds. She fell in her backyard on a cold December day, breaking her hip; she lay on the ground for four hours before a neighbor discovered her. “She's proof there are miracles. God wants her here,” Brenda said.

One of the largest forts ever built

With 5,000 acres, Fort Miles was one of the largest and most heavily fortified forts ever built. Its mission was to defend the Delaware Bay and Delaware River from enemy attack, and to protect domestic shipping to ports such as Wilmington and Philadelphia. It also maintained a naval minefield in the bay to prevent enemy ships from entering the waterway.

With construction starting before the war started, final work was completed by 1943. The base included 16-, 12- and 6-inch gun batteries as part of the 261st Coastal Artillery group.

While training was a mainstay at the fort, no enemy ships were ever fired on. However, the German U-858 submarine surrendered at the fort May 14, 1945.

The land was eventually turned over to the state of Delaware and became Cape Henlopen State Park. But before that, parts of the land were used by the military until 1990. The southern section of the base became Naval Facility Lewes from 1963 to 1981 where the military maintained a secret underwater surveillance operation on Russian submarines.

Starting in 2003, the Fort Miles Historical Association, in conjunction with Delaware State Parks, has undertaken a major restoration effort at the fort, including a museum in Battery 519, the fort's largest underground battery.