I ungracefully stomp along the marsh trail in my chunky boots. It is a quiet February morning, just a subtle breath of wind whispering between the snow-tipped golden grasses. The overcast day seems to emphasize the lack of all wildlife activity. Meandering along, alone in my own thoughts, I freeze as an eerie yelp-howl pierces the silence. My mind blanks. I am cornered at the end of the path, surrounded by frozen marsh on three sides. I slowly look behind me. (Perhaps a dog on a leash?) No one is on the trail. The high-pitched scream is moving toward me. I instinctively crouch lower. My curiosity compels me to look around the weathered observation platform that is blocking my view.

How often do humans cross paths with wild land mammals that are usually nocturnal? Rarely. How do we know these animals share our local forests, parks, wildlife refuges and urban neighborhoods? A highway of animal tracks in the mud and snow offers a rare winter glimpse into their nighttime travels and routines! How do they survive the colder temperatures? Most mammals are active, moving and eating to generate body heat throughout the coldest months. Of course there is an exception: the only “true hibernator” is the groundhog (Marmota monax). This year, the reluctant rodents will be chiseled out of their icy burrows!

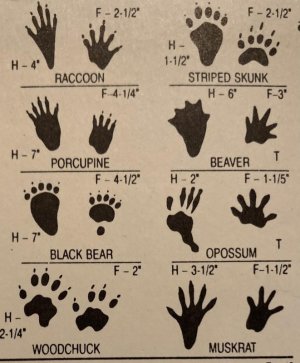

In the marsh, between the delicate toe impressions of shorebirds, large otter paw prints run side by side with raccoon tracks. The North American river otter (Lontra canadensis) is comfortable on land and a powerful swimmer. After a snowfall, otters create a network of “belly slides” (like sled trails) across the ice as they search for open water to feed on fish. Sharing common habitats, raccoons and opossums travel the edges of wetlands as well as urban habitats. Both mammals waddle as they walk with a side-to-side motion, leaving a pattern of hand-like paw prints. Look for the big opposable thumb, which helps it climb trees, on the hind foot of the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana).

On firmer ground, “hoppers” in motion leave behind a distinct track pattern. An eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) trail will show a series of tracks; each imprint will have a pair of long, narrow back feet side by side followed closely by off-centered, rounded paw prints. This pattern does not seem to conform to the anatomy of the animal, but a sitting rabbit is very different from a moving rabbit. Imagine the strength and grace of a gymnast. With the power in the back legs, the rabbit will bounce off the back feet and become airborne. The cottontail, from nose to toes, is stretched out in midair, poised to touch down on its padded front feet. After landing, it seamlessly swings its back legs forward so the back paws are now ahead of the front feet.

Activity powers these mammals through some of the toughest months of winter. You know, those days when 32 F seems downright balmy! Yet, as temperatures stay consistently below freezing and food is in short supply, many of these animals may enter a state of “torpor” to conserve energy. Torpor is a physical response to environmental stress. Mammals in torpor have a decrease in both body temperature and metabolism. Scientific understanding of torpor is constantly evolving. Current terminology suggests that hibernation is a form of torpor that is longer than 24 hours. True hibernators, such as groundhogs, may hibernate up to five months regardless of temperature and food availability. These animals need to “wake up” every few weeks to catch some sleep, because torpor is not sleep. They will lose one-quarter of their body weight, their temperature drops from 99 F to 37 F, and their heart rate plummets from 80-100 beats per minute to 5-10 beats. On the other hand, raccoons, skunks and opossums are light hibernators. These mammals are dormant for short periods of time during extreme weather events and are easily awakened. Their breathing and heart rate rapidly return to normal.

Our Cape Region has great locations, including the beach, to search for animal tracks. To quote a favorite author, “Tracks in the snow. Tracks in the snow. Who made these tracks? Where do they go?” Share the joy of exploring with “Tracks in the Snow,” a picture book by Wong Herbert Yee. By the way, the eerie scream and bark echoing across the marsh belonged to the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) trotting toward me. We made eye contact, but it paid me no attention.