Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of stories about shellfish farming in Delaware’s Inland Bays. After years of developing and passing regulations, farming has begun, and the first oyster cages are now in the water. In the coming months, reporter Chris Flood will explore the ins and outs of the new industry.

When it comes to oyster farming, John Shockley said Hoopers Island Oyster Co. has everything a person needs, from seed to shuck.

“We’re the most fully integrated oyster company on the East Coast,” said Shockley, standing on the southernmost tip of Old House Point along the Honga River of Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Shockley is a founding partner of Hoopers Island Oyster Co. and a third generation waterman who has spent his entire life on the small island about 30 minutes south of Cambridge. He was proudly displaying an oyster that was close to being ready, but it still needed some more Chesapeake Bay tender love and care. “I’ve spent a lifetime as a commercial fisherman.”

Rehoboth’s Chris Redefer was the first person to get cages – sinking and floating – into the water under Delaware’s new aquaculture program, which opened up small portions of Delaware’s Inland Bays to commercial oystering and clamming. He got his cages, oyster seeds, lines, floatation equipment and some general knowledge on using it all from the folks at Hoopers Island Oyster Co.

The company has three locations – equipment manufacturing in Cambridge, an oyster farm in Fishing Creek, and the nursery and hatchery in Crocheron. As is often the case when traveling by road from one Eastern Shore village to another, there’s no fast way to get to the farm or the hatchery. About a 20-minute drive south from Cambridge, through the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, is a T-shaped stop – a turn to the right goes down a peninsula to the farm; a turn to the left goes down another finger-shaped peninsula to the hatchery.

During a recent tour of the three facilities, Chris Wyer, senior manager sales and manufacturing, called the T-stop the point of no return. He was laughing, but roads are narrow; the water level is almost as high as the road. The brackish-water-loving vegetation is close and dense, and old, abandoned farm houses are well on their way to being reclaimed by Mother Nature.

The manufacturing and oyster farm locations are industrial. Floor space at the manufacturing facility is taken up by hand tools, power tools, supplies, machine parts, stock in various stages of completion and items ready to be shipped. The boatyard at the farm has oyster processing equipment, floating lines anchored to pilings and work boats docked.

Wyer said when other aquaculturists and watermen saw the equipment Hoopers Island was making for itself the manufacturing side took off. It got to the point where it made more sense to make the needed equipment on a commercial scale, he said.

The company has been in Cambridge since the summer of 2017. Before that, Wyer said, the manufacturing processes – fiberglass, machining, cage assembly – were all in different facilities, scattered in small buildings on the road out to the farm. The original commercial boat is still sitting in the front yard of the company’s original barn.

“We were very fragmented,” Wyer said. “We’re still learning ourselves, but things have definitely changed.”

Shockley was at the farm the day of the tour. He was helping load a skiff with bags of oysters that were close to being harvested, but needed some time in the water. The oysters had come from some of the farm’s floating cages.

“These are our premium product,” said Shockley, estimating each one would fetch 80 cents to $1 on the open market. “These might retail for $3 an oyster in a restaurant.”

If manufacturing and farm are the industrial sides of the company, the nursery and hatchery are a science lab with a million-dollar view. There are tanks on the outside dock flushing nutrients and clean water into silos from the bottom or top depending on the size of the oysters. There are walk-in coolers, lined with glass beakers and oxygen lines, full of algae the company has grown to feed the oysters in their microscopic stage of life. There are microscopes to observe oyster larvae and algae. Then there are five larval rearing tanks, each one about the size of three hot tubs, where the oysters spend the first part of their lives.

Natalie Clark, nursery manager, said the company gets its broodstock – male and female oysters – from Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Clark said they use species that have been successful in breeding. It’s similar to dog breeding, she said.

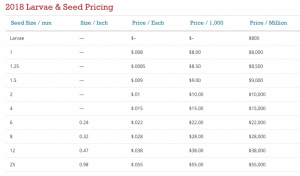

Clark said the oysters they grow are triploid, which means they’re sexually sterile and do not spawn. “They’re the oyster version of a mule,” she said, explaining the reason for using triploid is because the meat of the oyster is bigger and they grow faster because they’re not worried about reproducing. According to the 2018 larvae and seed pricing schedule found on the companies website, oyster costs range from $800 to buy 1 million larvae and $55,000 to buy 1 million 25 millimeters in size.

After the tour, on the way back to Cambridge, back through the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, Wyer said in the beginning, not all the local watermen were excited to have Hoopers Island get into oyster farming because it would be competing with traditionally harvested oysters. But, he said the company has contributed to artificial reefs, sold seeds to about 50 farmers last year and shipped their equipment all over the world.

Some clients, Wyer said, are traditional watermen who don’t want others to know they’re experimenting with oyster farming.

“We’re trying to be successful, but it’s better for everyone if we’re working together,” Wyer said. “There’s been a lot of growth in the market over the past few years, but it’s still a niche market.”

Hoopers Island Oyster Co.’s nursery and hatchery by the numbers:

Natalie Clark, Hoopers Island Oyster Co. nursery manager, complied the following facts. Growing the algae is typically started in January, with production of oyster larvae around mid-March. The hatchery will finish up at the end of September; the nursery will go into November.

- A bundle of 5 million oyster larvae is about the size of a baseball.

- A milliliter of algae can have up to 20 million algae cells in it.

- A million, 1-millimeter size oysters take up about 1 liter of volume.

- One larval rearing tank holds 1,500 gallons of water.

- About 6,000 gallons of filtered salt water is used each day for just the hatchery.

- One larval rearing tank can hold up to 30 million mature oyster larvae.

- Under the right conditions, oyster larvae can double their size every 24 hours.

- A typical female oyster can have upwards of 10 million eggs.

- On average, 25 percent to 30 percent of what the hatchery produces turns into an actual oyster.

- During the growing season, over 5,000 Pasteur pipettes will be used to take samples.

- During the growing season, more than 1,000 hours will be spent on the microscope.

Chris Flood has been working for the Cape Gazette since early 2014. He currently covers Rehoboth Beach and Henlopen Acres, but has also covered Dewey Beach and the state government. He covers environmental stories, business stories and random stories on subjects he finds interesting, and he also writes a column called Choppin’ Wood that runs every other week. He’s a graduate of the University of Maine and the Landing School of Boat Building & Design.