Dover's small step in the space race

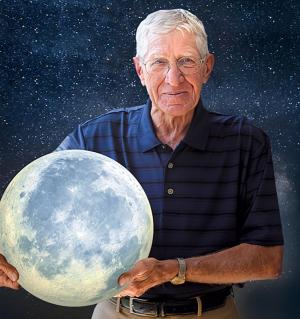

The 50th anniversary of the moon landing was a whirlwind for Homer Reihm. He was interviewed by “CBS Sunday Morning,” ABC's “Good Morning America” and a host of other publications.

But the 80-year-old, who nowadays splits his time between Dover and Dewey Beach, took it all in stride. As program manager at International Latex Company Inc., he ran the Apollo contract from 1965-73 – a real coup for a little-known government and industrial division of Playtex situated on the far side of Wesley College's playing fields.

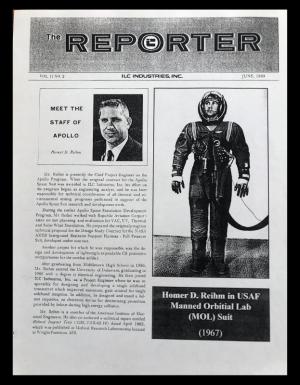

Reihm was fresh out of college with an electrical engineering degree from University of Delaware when he heard about ILC's nascent experiments with spacesuits. He said a team of ILC engineers had the foresight to develop a suit – at the time called a convolute – that was more flexible, offering greater movement compared to the rigid designs that Mercury and Gemini astronauts had worn for their orbits in space.

“It looked to me that these guys had a leg up on it,” Reihm said. “The technology of Playtex fit right into what they were doing, and they had been working on a suit since about 1957.”

The convolute was rugged but flexible, made mostly of heavy-duty Dacron, nylon and rubber, he said. Riblets that easily compressed and expanded like an accordion provided mobility in the key joints of the 17-layer suit, he said. “This was a quantum leap above Mercury and Gemini spacesuits, which floated in a single posture,” Reihm said. “You had trouble moving the big joints, and about all you could do was move your fingers or your wrist if you had to fly the stick or retrieve a sample.”

Standing about 6-feet tall and weighing 180 pounds, Reihm, a college baseball player, had the same athletic build as the optimally fit astronauts, making him the perfect model for the suit during its production.

When the suit was ready to go, film footage shows an employee wearing the spacesuit moving about on Wesley College's football field, across the street from the ILC workshop. The unidentified man even kicks a few field goals through the football crossbars.

“They finally had a product that they could produce and reproduce reliably that looked like a winner,” he said.

Film footage of the suit in action sealed the deal.

In 1962, NASA chose ILC's spacesuit over BF Goodrich, maker of the Mercury spacesuit, and David Clark, a Massachusetts company that made the Gemini spacesuit.

“NASA said they liked the suit and the video of the suit,” Homer said.

The clincher, though, was that Hamilton Standard got the prime contract for the spacesuit because of its oxygen and environmental backpack, and Hamilton took a lot of credit for ILC's spacesuit work, Reihm said.

ILC engineers, however, were undeterred and kept improving the mobility and flexibility of their spacesuit. Specifically, Reihm said, engineers designed a helmet that gave astronauts more neck and shoulder movement compared to the crash helmet design up to that point.

In 1965, ILC again beat out major competition for the spacesuit contract.

“Our suit won hands down,” Reihm said. “The main reason is we put a bubble dome helmet on it. We said you don't need a crash helmet. You put an impact pad on the back when he's in the couch during launch and his head will be against that pad.”

From 1965-73, Dover was the hub of activity for U.S. spacesuits, and Reihm was running the show.

Astronauts would fly into Dover Air Force Base from Houston, Texas, and spend the day for fittings at the ILC facility on Pear Street, a sleepy area of Dover next the railroad tracks, about six blocks from downtown. “The suits were all custom made,” Reihm said.

About 150 people worked on the suits – three for each astronaut and two for each backup – about 15 for every mission. At any given time, Reihm said, there were five or six suits in various stages.

But production stopped when an astronaut took the floor.

“We would call an all-hands meeting on the production floor, and a crew member would speak to the people and tell them how critical their job was, and that their stitch could be the stitch that saves their lives,” Reihm said. “It was really a morale booster and a focus on just how important it was what they were doing.”

In 1968, Reihm attended the launch of Apollo 7 at Cape Canaveral in Florida – the first launch that used the ILC spacesuits. It was also a tense moment following the fatal launch a year earlier, but everything went as planned. “It made us feel good. There were no problems,” he said.

When Apollo 11 took off in 1969, Reihm was at the command center in Houston for technical support. While the world watched Neil Armstrong take his first steps on the moon, Reihm was steadily watching the spacesuit. “I was concerned that we may have overlooked something, and hoped we wouldn't be snake bit by that,” he said.

Only when the astronauts were climbing back into the capsule did he breathe easy. “By the end of the mission, I was enjoying it,” he said.

“We knew we were making history. We were a big part of the space race, and we knew this was America on the line. We had the world behind us, and everyone at ILC was elated.”

Melissa Steele is a staff writer covering the state Legislature, government and police. Her newspaper career spans more than 30 years and includes working for the Delaware State News, Burlington County Times, The News Journal, Dover Post and Milford Beacon before coming to the Cape Gazette in 2012. Her work has received numerous awards, most notably a Pulitzer Prize-adjudicated investigative piece, and a runner-up for the MDDC James S. Keat Freedom of Information Award.