Seven-year-old's death ruled suicide

Three months ago, on a cloudy but mild Tuesday in September, second-grader Nathan Leppo died in a home in Oak Orchard. Only 7 years old, he was a sweet and funny child, relatives say, always ready with a hug.

But something happened that day when this young boy took his own life.

For months, the Cape Gazette has sought an explanation of how the boy died – culminating in a Freedom of Information Act request and subsequent challenge to its denial. Without saying his name, officials recently publicly confirmed a 7-year-old boy died Sept. 22 by suicide.

Rumors of the boy's suicide had spread throughout the community following his death. Even family members had questions. Nathan's aunt, Briana Leppo, said, before Nathan died, she contacted a state family services agency numerous times about caring for Nathan to no avail.

“I called for three weeks before Nathan's death to try to get information on how to get placement. Nobody returned my calls,” she said. “That says to me, someone dropped the ball. All I wanted was information on how to get placement.”

Briana Leppo said the boy's father, Wayne Leppo, had custody of Nathan from the time he was 2. Wayne Leppo could not be reached for comment. Delaware court records show his mother, Kayla Marie Brown, had been transferred to an out-of-state facility, following several convictions for drugs, theft and violation of probation.

Briana said her brother had moved to new accommodations, and a caseworker told him that Nathan could not stay there. Briana said she doesn't know why family services allowed a woman living in an efficiency apartment on River Road to have guardianship of Nathan. She said the death certificate, which she obtained from the funeral home that handled Nathan's funeral, states the cause of death was “asphyxia by neck compression, hanging from shower-spray hose.”

“If you're telling me that my brother isn't making good decisions about where he is living, why would you let him choose where Nathan stays?” she asked. “This lady lived in an efficiency apartment with no bed for him to sleep.”

Briana said the Division of Family Services had been involved with Nathan before, and they knew his home life was unstable.

“How many times does a state agency need to get involved before they take the kid out of the situation?” Briana questioned. “Parents have rights, but the state should know when it's not good for the child.”

Suicide at 7 rare

According to the death certificate, officials ruled Nathan Leppo's death a suicide – a manner of death so uncommon for his age that statistics are scarce. Experts say it is rare for a young child to understand the implications of ending his life.

“Suicide under the age of 10 is a very rare and unusual event. In some ways it's hard to understand how a 7-year-old would have the cognitive capacity to understand what death means,” said Maureen Underwood, clinical director of the Society for the Prevention of Teen Suicide.

She said, in general, a young child who commits suicide would do so impulsively without an understanding of the real consequences.

Dr. Joseph Zingaro, a local clinical psychologist, said a 7-year-old child has no cognitive ability to understand the permanence of death.

“There would be something unique about what is driving that behavior that may or may not make sense to adults around them,” he said. “You have to look at what the stressors are to them, not anyone else.”

In some instances, Zingaro said, he believes a child's death could be called a suicide when in reality the child was trying to get attention. For example, he said, if a child takes too many pills to get attention, the result can prove fatal.

“What we say after the fact was a suicide could be an accident, but we don't have the information needed to piece it together,” Zingaro said.

Self-inflicted deaths among children under 10 are so rare, no statistics are kept by the National Violent Death Reporting System because very young children cannot understand the consequences of their actions, said Courtney N. Lenard, health communication specialist for the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

“They lack the capability to understand the finality of ending their life and, developmentally, they may lack the coping skills to deal with the stressors that contribute to their suicidal feelings,” she said.

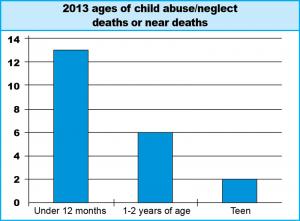

The reporting system covers all types of violent deaths – including homicides and suicides – in all settings and for all age groups. According to 2013 statistics, suicide is the third leading cause of death for children 10-14. The number rises to second for ages 15-24 and also 25-34. For children younger than 10, suicide does not make the top 10 causes of death.

However, Lenard said Centers for Disease Control data for suicide injury deaths 2009-13 for children between ages 5 and 9 show 32 children ages 5-9 died from suicide. This is out of more than 100,000 cases – a rate of .03 percent – the CDC chart notes.

State withholds child autopsy findings

Hearing reveals four child deaths since May

When a 7-year-old boy died in September of an apparent suicide, it served as a stark reminder that life is fleeting. It also resulted in state government officials tightening their grip on public information about deaths in Delaware.

Questions swirled throughout the community following Nathan Leppo's death, asking how a healthy child could die in a home of someone not related to him. Prompted by public interest, the Cape Gazette delved for answers, but state officials refused to release information, citing confidentiality and an active investigation.

This secrecy remained until a routine hearing Nov. 30 unexpectedly cracked open some detail surrounding Nathan's death.

Sen. Gary Simpson, R-Milford, attended the confirmation hearing of Carla Benson-Green, incoming secretary of the Department of Services for Children, Youth and Their Families, and he took the opportunity to ask questions about child deaths.

“I had heard there was a higher number of deaths since Memorial Day, but that's all I knew,” Simpson said. “I didn't have any background on any of them.”

Simpson learned there were four child deaths since May, all in Sussex County – one, a 7-year-old, was a suicide.

Because of Simpson's questioning, the Division of Family Services released information that it previously had insisted was confidential. Simpson said had he known information on Nathan's death had been withheld, “I would've asked more questions.”

In addition to Nathan's death, Joseph D. Smack, executive assistant for the Division of Family Services, said a 3-month-old child died in September from abuse; a 1-month-old child died while co-sleeping with a caretaker in September; and a 3-month-old died in October of sudden unexpected infant death syndrome. The three infant deaths were connected to heroin use by their caregivers, he said. The parents of the 3-month-old were charged Dec. 10 with murder by abuse in the death of their child.

Since September, Smack would neither confirm nor deny whether Nathan was under state care in any capacity. On Dec. 1, he said the boy was with a caregiver who was receiving assistance from the Division of Family Services. Smack said the boy was not in foster care, and he would not say whether the caregiver had guardianship.

Referring to information released at the hearing, Smack said, “This was a unique situation where we were asked to share information, and we were able to do so while keeping the anonymity of the families involved in our services. Questions like this aren't usually asked during a confirmation hearing.”

But since they were asked by a public official during a public hearing, Smack said, the information became public.

“When it was aired in public, we had to answer questions,” he said.

Gazette seeks cause of death

On Oct. 26, the Cape Gazette requested information under the Freedom of Information Act from the Division of Forensic Science, under the Department of Safety and Homeland Security. The request asked for the autopsy findings, specifically the cause and manner of Nathan's death.

Department of Safety and Homeland Security Spokeswoman Kimberly Chandler said the Division of Forensic Science would provide no cause or manner of the boy's death because autopsies are investigative reports not subject to FOIA. She said only next of kin can receive an autopsy report, unless criminal prosecution is underway, which would delay release of the report.

Chandler cited state law that protects personal information from public release, referring to a 2005 Attorney General's opinion that asserted, “autopsy information is exempt under the Delaware FOIA.” This opinion was issued after a Chancery Court decision involving Rehoboth Beach businessman Duane Lawson, who was found dead in the front seat of his burned BMW, parked in a Rehoboth parking garage. His wife, Lisa, filed a lawsuit to block the release of her husband's autopsy results by Rehoboth Beach police, who had intended to release information to news agencies requesting it.

Chancery Court denied Lisa Lawson's preliminary injunction request to prevent Rehoboth Beach police and the former Medical Examiner's Office from releasing Lawson's autopsy results, but Delaware Supreme Court eventually ruled in favor of Lisa Lawson, based in part on Delaware's 2002 Health Record Privacy Statute and interpretation of existing state statute.

Chancery Court also noted that autopsy information is exempt under Delaware FOIA, which Chandler cited in denying release of the manner of Nathan Leppo's death.

Under further advice from the Attorney General's Office, Chandler said, autopsy results are considered private because of a state statute that covers, “Any records specifically exempted from public disclosure by statute or common law.”

However, the Division of Forensic Science and the Attorney General's Office failed to note a relevant interpretation written in 2006 by Deputy Attorney General A. Ann Woolfolk. Woolfolk wrote the opinion after the Medical Examiner's Office asked how to proceed in the wake of the Lawson case. She wrote that when someone dies, officials may tell the public whether the death is natural, accidental or homicide.

Woolfolk wrote that the Supreme Court may have openly discussed Lawson's manner of death only because both sides had agreed to discuss it. However, she added, “In our view, this would be a draconian view of the Lawson decision and is not what the Supreme Court intended.”

Today's Attorney General's Office has taken that draconian view.

On Dec. 4, the Attorney General's Office closed down even the little bit of information – manner of death – that previously had been public information.

The Cape Gazette's appeal of its FOIA request denied by the Division of Forensic Science was also denied by the Attorney General's Office. Deputy Attorney General Lisa M. Morris wrote that even manner of death is considered autopsy information that is exempt from disclosure under FOIA as part of an investigative file compiled for law enforcement purposes.

Morris' denial, in part, reverses the long-standing practice based on Woolfolk's 2006 interpretation, of releasing at least manner of death.

While acknowledging Woolfolk's interpretation, Morris wrote, “There is no statute or case law that requires such a disclosure in all cases. Given the private nature of the Medical Examiner's files, and because the decedent is a minor, the Division argues that manner of death is not a required disclosure in this case.”

Under the former Medical Examiner's Office, the public received manner of death information for accidents, homicides and suicides.

In 2013, one death near Indian River Inlet and a second death discovered after a house fire were both listed as accidents. Also, in 2013, the manner of the death of a man found in a burning car near Delmar was released as suicide.

Even in the controversial Lawson case, the Medical Examiner's Office released the manner of death as accidental.

In 2014, the Medical Examiner's Office, which operated under the Department of Health and Social Services, was dissolved after a drug-tampering scandal erupted. Six months later, the Division of Forensic Science was created and placed under the Department of Safety and Homeland Security.

Report on death expected in 2016

It could take months for state officials to release a report on Nathan Leppo's death, and even then, questions may remain.

Smack said the Child Death Review Commission should complete a report in 2016 on the boy's death.

Anne Pedrick, executive director of Delaware's Child Death Review Commission, said when the commission is notified of a child's death, and there is indication of abuse or neglect, they will consult with the Child Protection Accountability Commission to determine whether the case merits further review. If so, she said, the Child Death Review Commission would review all the circumstances surrounding the child's death, but it would not issue a report until the case is cleared. Issues with the child welfare system are also addressed and shared during the initial review, she said.

Police say they have completed their investigation of the case, and no foul play is suspected.

Still, despite repeated requests for information, state officials in charge of autopsy information and death certificates refuse to release any information specifically related to Nathan's death.

Adrianna Rodriguez, an attorney with Holland & Knight in Washington, D.C., said generally, a dead person does not have the right to privacy. However, the 2006 Supreme Court of Delaware decision in the Lawson case extended privacy rights to his family.

Rodriguez said Delaware courts have held that postmortem reports – including autopsy reports, toxicology results and death certificate – are exempt from disclosure under FOIA if they are part of an investigation.

In Delaware, she said, “The investigation exemption is very broad, and, unlike in some states, specifically includes records of completed investigations. So even if police briefly investigated the death to ensure it was not suspicious, that is enough to call it an investigative record.”

A Freedom of Information Act advocate says Delaware government should be moving toward more transparency, not less.

John Flaherty, president of Delaware Coalition for Open Government, said the public needs checks and balances in order to trust government. Otherwise, officials are merely hiding behind a veneer of open government.

Commenting on the Cape Gazette's effort to obtain cause and manner of death, he said, “I can see no public policy reason why they shouldn't divulge this information. FOIA was created to allow you and I to monitor the activities of our public officials. They are interpreting state law contrary to the intent of the FOIA.”

Without access to information, he said, government officials are unaccountable and, at worst, can become corrupt.

“They need to construe the open government law liberally and not hide behind the legal curtains that are there to thwart any kind of public inquiry,” Flaherty said.

Melissa Steele is a staff writer covering the state Legislature, government and police. Her newspaper career spans more than 30 years and includes working for the Delaware State News, Burlington County Times, The News Journal, Dover Post and Milford Beacon before coming to the Cape Gazette in 2012. Her work has received numerous awards, most notably a Pulitzer Prize-adjudicated investigative piece, and a runner-up for the MDDC James S. Keat Freedom of Information Award.