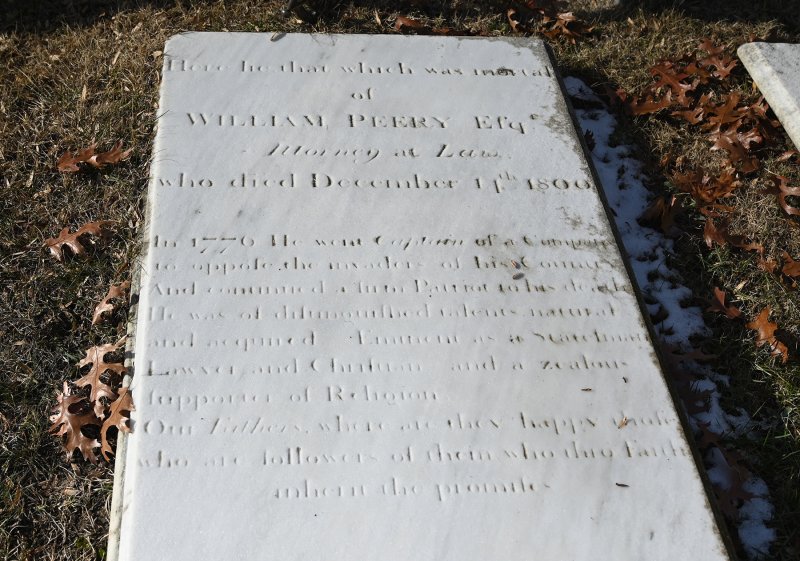

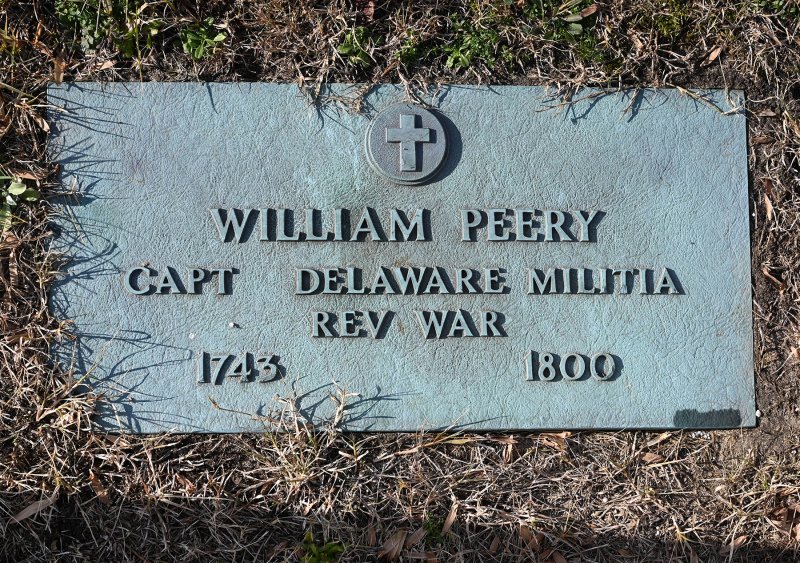

In a time when Sussex County looked much different, William Peery owned more than 1,000 acres of land in the Cool Spring area west of Lewes. In fact, the man who played a major role in winning support in Sussex County for American independence is buried at Coolspring Presbyterian Church.

Perry was considered a patriot, a supporter of the Whig party, which favored independence in the late 1700s. At the time, the majority of Sussex Countians considered themselves loyalists, aligning themselves with the Tory party, which opposed independence.

“Early in his political career, William Peery joined the opposition to British policies perceived as oppressive,” said Bruce Bendler, a University of Delaware adjunct professor and Delaware Public Archives researcher for nearly 50 years. “Such opposition at first won nearly unanimous support in Sussex County, but when that ‘I’ word began to emerge – independence – Sussex Countians began to back off a little bit, and the majority of them became loyalists.”

When the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence July 4, 1776, Sussex County had already become a hotbed of opposition to that decision, Bendler said during a presentation at the Delaware Public Archives in Dover.

“There was no such thing as scientific polling back then, but if there had been, Sussex County would’ve surely voted overwhelmingly against independence,” Bendler said.

But, Bendler said, “Peery clearly gave a voice to the minority of Sussex Countians who did not wish to remain under sovereignty of his majesty King George III.”

Peery was a farmer, sawmill operator and lawyer. He joined the military in 1775, serving in the company commanded by David Hall, for whom the Lewes chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution is named.

A year later, Peery served as captain of an independent company assigned to protect the Delaware Bay and River from the loyalists of Sussex County. Peery and Henry Fisher, another notable person in Lewes history whose home remains on Pilottown Road, wrote a letter to John Hancock in 1777 to describe the situation in southern Delaware. They said American ships of war could not lie safely in the harbor area without a military guard. A few weeks later, they reported to Hancock that Sussex loyalists actually boarded British ships.

In a sign that support for independence was lacking in Sussex County, Bendler said, in the first election after the declaration was signed, residents voted for a slate of candidates who were lukewarm at best toward the American cause.

“Prospects the next year didn’t look much better,” Bendler said.

Peery wrote a letter to Caesar Rodney, one of Delaware’s signers of the Declaration of Independence. In the letter, he said, “Tories and their allies circulated vicious stories to influence the minds of the vicious multitude here.”

Peery responded to those Tory actions by trying to force people to take an oath of allegiance to the American cause in order to vote. Tory leaders retaliated by capturing Fisher and attempting to beat him, but patriot militia members rescued him.

The election was postponed until March 1778. A week later, the Sussex County sheriff sent the returns to the legislature. Peery was among several elected who were at least partially in the patriot camp. Whigs now controlled Delaware’s legislature for the first time since independence was declared.

Opposition remained strong in Sussex County. Peery and his colleagues still sought to prevent their opponents from voting. Peery and his political ally Nathaniel Waples debated the efficacy of posting guards along the road leading to Lewes, which was the county seat during that time.

When the legislature reconvened, a petition signed by 50 people alleged they faced intimidation, saying when they arrived at the courthouse in Lewes to cast their ballot they were greeted by armed guards blocking the entryway for anyone inclined to vote against Whig candidates. They also alleged the armed guards along the road to Lewes prevented others from even arriving to vote. The heavy-handed approach was the one preferred by Waples. After a formal investigation into the matter by the legislature, the Sussex County Whigs were seated.

Peery served two more terms in the House of Assembly, now known as the House of Representatives. He continued to focus on supplying Delaware’s militia and its regiment in the Continental Army. After leaving the legislature, Peery continued his efforts on behalf of the military. In November 1782, the legislature appointed Peery to settle accounts between the state and the Federation of Governments.

In the 1790s, as the country’s political party structure began to take shape, Peery aligned himself with the Democratic Republicans, opposing Delaware’s emergence as a Federalist stronghold.

“Again, Peery found himself in a political minority in Sussex County, which became a bastion of Federalist strength,” said Bendler. “I’ve often said that Sussex County, from the 1790s up until the early 1820s, was almost devoutly and religiously Federalist.”

As was common in Colonial times, Peery enslaved six people – two men and four boys. He died in 1800. He divided his estate between his widow and two adopted sons.

A July 2, 1957 article in the News Journal describes a dedication ceremony hosted by the Daughters of the American Revolution that honored Peery by placing a patriotic marker at his grave. Attending the ceremony were Peery’s descendants, who the article says then went by the last name of Perry.

Bendler’s presentation also featured a profile of Boaz Manlove, a native Sussex Countian who fell into the loyalist camp, with his actions forcing him to flee Delaware. To watch the full presentation, go to youtube.com/watch?v=WF6akM0kFzA.

Nick Roth is the news editor. He has been with the Cape Gazette since 2012, previously covering town beats in Milton and Lewes. In addition to serving on the editorial board and handling page layout, Nick is responsible for the weekly Delaware History in Photographs feature and enjoys writing stories about the Cape Region’s history. Prior to the Cape Gazette, Nick worked for the Delmarva Media Group, including the Delaware Wave, Delaware Coast Press and Salisbury Daily Times. He also contributed to The News Journal. Originally from Boyertown, Pa., Nick attended Shippensburg University in central Pennsylvania, graduating in 2007 with a bachelor’s degree in journalism. He’s won several MDDC awards during his career for both writing and photography. In his free time, he enjoys golfing, going to the beach with his family and cheering for Philadelphia sports teams.