It’s not a matter of if Lewes will flood, but when. The city’s intimate relationship with waterways helped fuel its prosperity and continues to contribute in a meaningful way to the lives of its residents and visitors; however, rising sea levels and more intense storms have put areas like Cedar Street at high risk for future daily flooding.

Thanks to a grant from the Delaware Emergency Management Agency, the city performed a flood risk reduction analysis for the western end of Cedar Street. As an emergency evacuation route, Cedar Street is needed for safe travel during natural disasters.

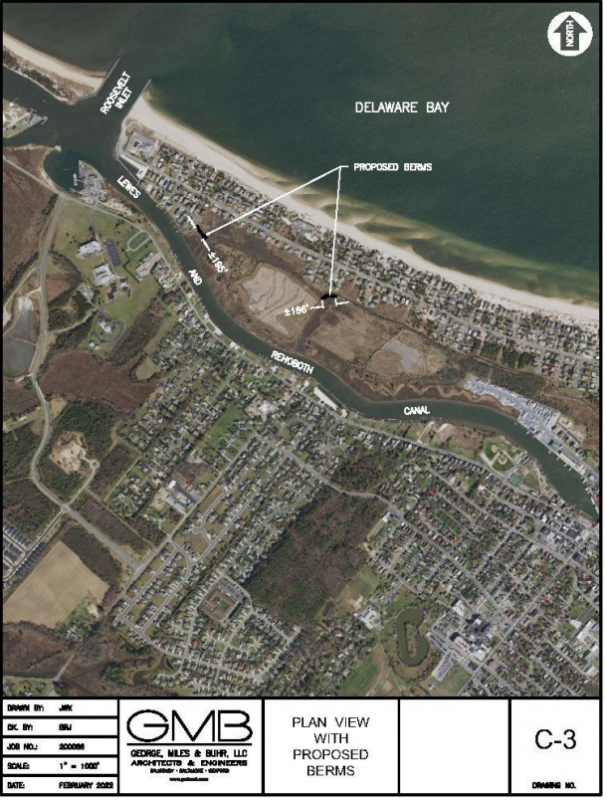

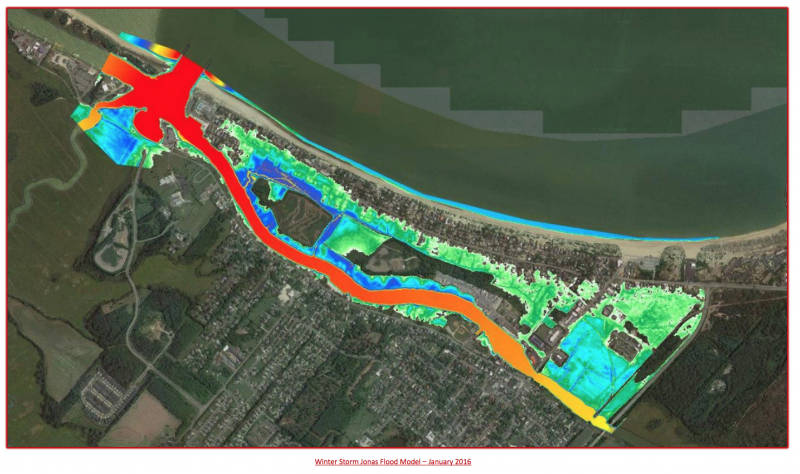

Focusing on the water of the Delaware Bay, Roosevelt Inlet and Lewes-Rehoboth Canal and impact on homes west of Indiana Avenue, the study looked at threats from severe and coastal storms, intense precipitation and tidal surges. George, Miles & Buhr used advanced engineering studies and geothermal imaging to detail water levels created by winter storm Jonas in 2016, a 1998 nor’easter, and a king tide in 2020.

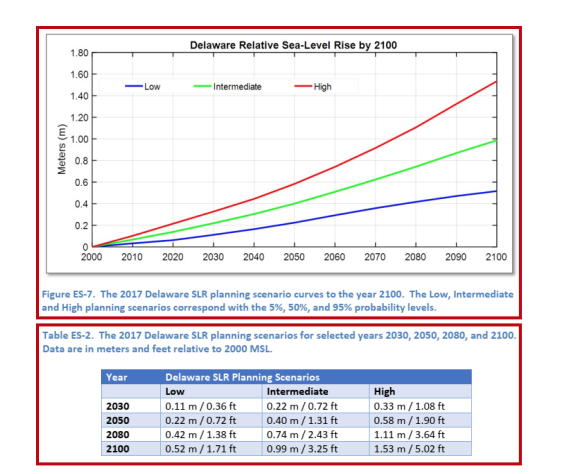

Jonas was the highest recorded tide at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association’s tide gate near the Cape May-Lewes Ferry terminal. It saw a rise of 6.63 feet, higher than the infamous 1962 nor’easter. The 1998 nor’easter climbed to 5.88 feet, while the king tide of 2020 reached 4.62 feet, providing a comparative look at the higher end of Delaware’s sea-level rise projections for 2100, which could climb to as high as 5.02 feet, but only has a 5% probability of occurring. For the analysis, GMB used the intermediate sea-level rise model, which has a 50% probability. It predicts a rise of 1.31 feet by 2050 and 3.25 feet by 2100.

The National Weather Service classifies a flood in Lewes as when water rises 3.37 feet; it issues a coastal flood advisory at 3.67 feet. GMB’s research indicates Lewes will be in a minor flood stage nearly every day by 2050 if the intermediate projections are realized. If an additional 3 inches are added, GMB said Lewes will be under a coastal flood advisory on an average day without precipitation or tidal surges by that time.

The study relied heavily on public feedback, including photographs taken during the flooding events. Photos showing the emergency evacuation route underwater highlighted the nuisance not only during the bigger storms, but during the times when a heavy rain coincides with a tidal surge. While the photos were needed to illustrate flooding concerns on Cedar Street, they also show something that could occur on a daily basis in the future.

Addressing the Lewes Board of Public Works at its May 25 meeting, GMB’s Certified Floodplain Manager Brent Jett said Lewes floods from the back side via Roosevelt Inlet, and during nor’easters, the Atlantic Ocean enters into the Delaware Bay, surging the tide through the inlet and into the Lewes-Rehoboth Canal. Canary Creek and surrounding waterways connected to the inlet and canal also experience an influx of water. Lewes Beach sits at a higher elevation than Cedar Street, and the areas around the canal are more exposed to sea-level rise than the physical beach.

“But it’s not just tidal surges that cause problems in that focus area for this study; we’re also getting more intense rains,” Jett said. “It rains differently. Now we’re getting 2 inches of rain in half an hour, instead of an inch of rain in over 24 hours.”

Traditional stormwater management has been modeled on the previous rate of rainfall, allowing for accumulated water to slowly dissipate over an extended period of time. According to Jett, the University of Maryland has begun looking at how intensely the rain is falling; however, the time period is not yet long enough to collect enough data to form an informed hypothesis. In the meantime, development continues, and as more development occurs, more stormwater management systems are built that tap into a drainage system that eventually leads to the canal.

Jett said he believes the water going to the canal isn’t a huge problem because the water moves quickly, but it also moves both ways and comes from as far as Georgetown. The volume of water coming into Cedar Street is projected to increase regardless of what steps are taken, and Jett said the solution is to manage the water entering the area. There are healthy marshes that are fed by the tides regularly and can help with excess water, he said, but if it is high tide and the marsh is already full, the water has no other choice but to encroach onto people’s backyards and spill out onto roadways.

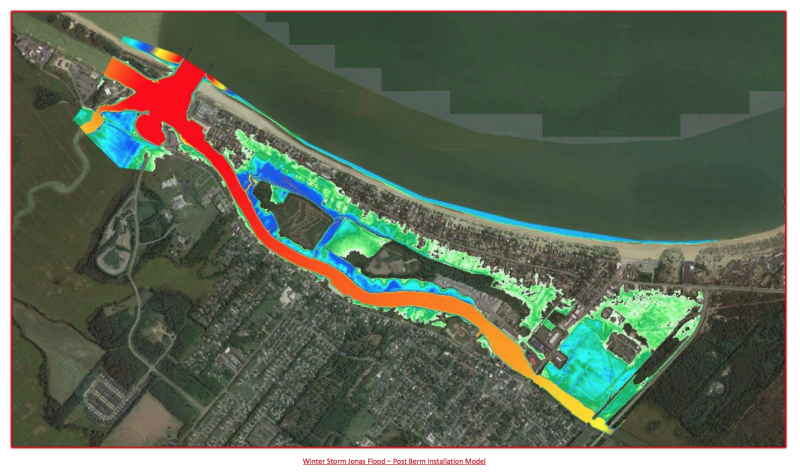

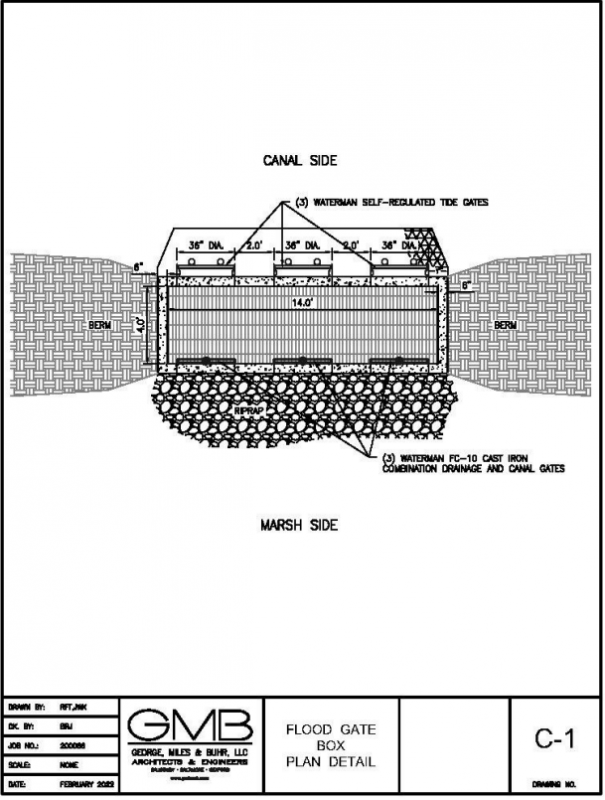

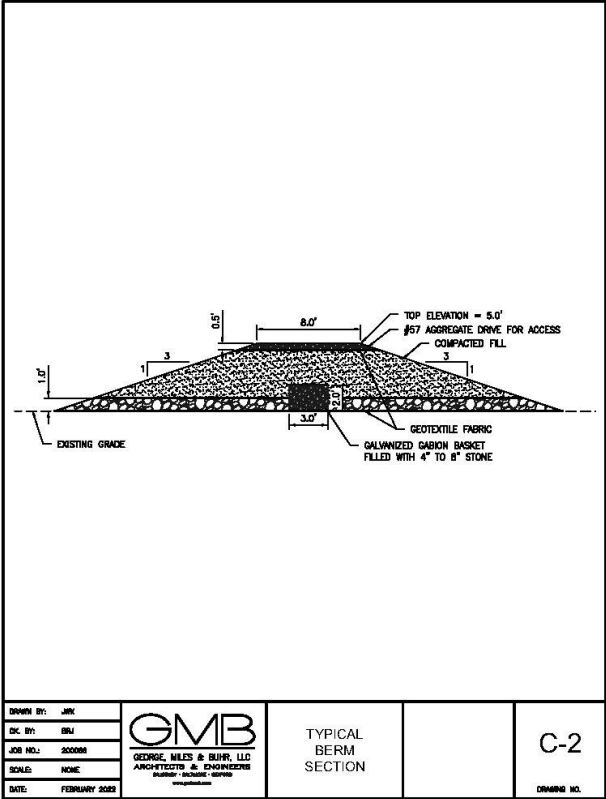

According to Jett and GMB, the best solution for Lewes is to install a berm-type mitigation system that would improve existing berms at the end of the Charles Mason Way cul-de-sac and the northernmost U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredge spoil area in the wetland marsh. They have also proposed an additional berm between both Corps spoil sites toward the end of Camden Avenue, where a main gut has formed from the canal that feeds floodwaters to the backside of the marsh area. A solid berm would cut off water needed to nourish the marshland, and Jett has recommended installing a concrete structure at each gut with gates to allow for the controlled passage of water.

Three self-regulating tide gates and three manually operated sluice gates will be installed at each structure. The self-regulating gates will remain open during a normal tide cycle to allow for the free flow of water into the marsh and positive drainage during precipitation. If tides breach normal levels, the gates will float and shut, cutting off the tidal surge encroaching into the marsh. The mechanism allows water to rise on the canal side of the berm, but not the Cedar Street side. Following the ebb of tide, the self-regulating gates will open and resume normal operations.

In the case of predicted extreme tides, sluice gates can be manually closed during the low tide to prevent the backwater elevation from rising with the surge. The gate can remain closed until the surge passes, then be opened to resume normal tidal functions. The berms will have an elevation of 5 feet above sea level, and, GMB says, this would prevent wrap-around flooding.

Total costs for the berms is currently estimated at about $3.27 million. Before moving forward with recommendations, mayor and city council want to see if BPW is able to properly maintain the proposed berms. The berms are designed to be driven to, and any equipment needed for repairs would be able to come with the repair worker out to the site. BPW believes it can effectively maintain the gates.

GMB engineer Charlie O’Donnell said he believes the project would be a win for the city because it is one of the areas identified in a 2015 study as being vulnerable. Mayor and city council were planning to discuss the next steps at a June 13 meeting.

Aaron Mushrush joined the sports team in Summer 2023 to help cover the emerging youth athletics scene in the Cape Region. After lettering in soccer and lacrosse at Sussex Tech, he played lacrosse at Division III Eastern University in St. David's, PA. Aaron coached lacrosse at Sussex Tech in 2009 and 2011. Post-collegiately, Mush played in the Eastern Shore Summer Lacrosse League for Blue Bird Tavern and Saltwater Lacrosse. He competed in several tournaments for the Shamrocks Lacrosse Club, which blossomed into the Maryland Lacrosse League (MDLL). Aaron interned at the Coastal Point before becoming assistant director at WMDT-TV 47 ABC in 2017 and eventually assignment editor in 2018.