Henlopen Acres’ Henry DeWitt involved with Ultima Thule expedition

Henlopen Acres resident Henry DeWitt occasionally dons full Scottish regalia and plays bagpipes for ceremonies in the Rehoboth Beach area. That’s earthly stuff.

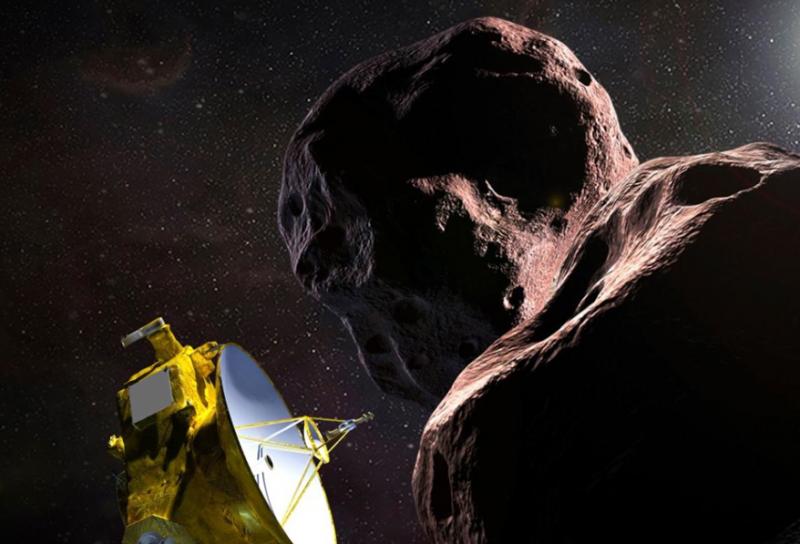

In his life that pays the bills - as a physicist and software developer - DeWitt’s work plays a role in man’s farthest explorations into the known universe. When the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s New Horizons spacecraft early on New Year’s Day passed by an asteroid 4 billion miles out in space known as Ultima Thule, DeWitt’s work was in the mix. He helped write software for the New Horizons simulator that ensures electronic commands beamed to the actual spacecraft will accomplish what they’re intended to accomplish.

“When a command load of data is put together to direct the desired tasks of the spacecraft, the simulator first ingests that data and then simulates everything the spacecraft will do with the command,” said DeWitt. “The simulator software can show us a day’s worth of operations on the spacecraft in just a couple of minutes.” If the command load of data the simulator ingests doesn’t result in the desired tasks, project directors can find the problems and correct them before sending the commands to the actual spacecraft.

Among the couple of thousand tasks the spacecraft can accomplish are such things as moving its position in space - known as its attitude - so it can be best oriented to make digital images of objects such as the Ultima Thule asteroid. In July 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft accomplished its original mission of passing close enough to the little planet of Pluto to send back the first close-up recorded images. It took 10 years for the nuclear-powered spacecraft - traveling at 35,000 miles per hour - to reach Pluto, and another three years to reach Ultima Thule. DeWitt said New Horizons has enough nuclear fuel left to keep it moving farther out into the universe for another five to 10 years.

The simulator software DeWitt wrote for the New Horizons project took about a year of development. The software used what is known as legacy code from previous simulator software that he and others also developed for other spacecrafts, as well as new code. And the New Horizons simulator software has been evolving through the years since the spacecraft launched.

“It takes four or five hours for just one bit of data to make it from the spacecraft back to Earth. The data rates are horrendously slow. It will take more than a year for all the data collected by this latest fly-by of Ultima Thule to make it back to Earth,” said DeWitt. “The spacecraft is programmed to send back the best shots early.”

Because it takes so long for commands and responses to travel back and forth between spacecraft and Earth - especially when they’re more than 4 billion miles apart - the role of the simulator in testing command loads is critical. Once the commands have been sent to the actual spacecraft, they have to be right. “You don’t get a second chance - especially on a fly-by,” said DeWitt. “At that point all you can do is hope that it does what it’s supposed to. There’s nothing more you can do about it.”

DeWitt does his work under contract with Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, a federal government research facility operated by the university. “I was under contract through Jan. 1,” he said.

He isn’t sure what his status is now, but unlike a lot of NFL football coaches who recently lost their jobs, DeWitt has a winning record. Time will tell. But there is one thing he is certain of: “It’s an interesting life.”