University of Delaware President Pat Harker visited Lewes last week and spent time with local members of the press including Molly Murray of the News Journal and Melissa Steele and myself of the Cape Gazette.

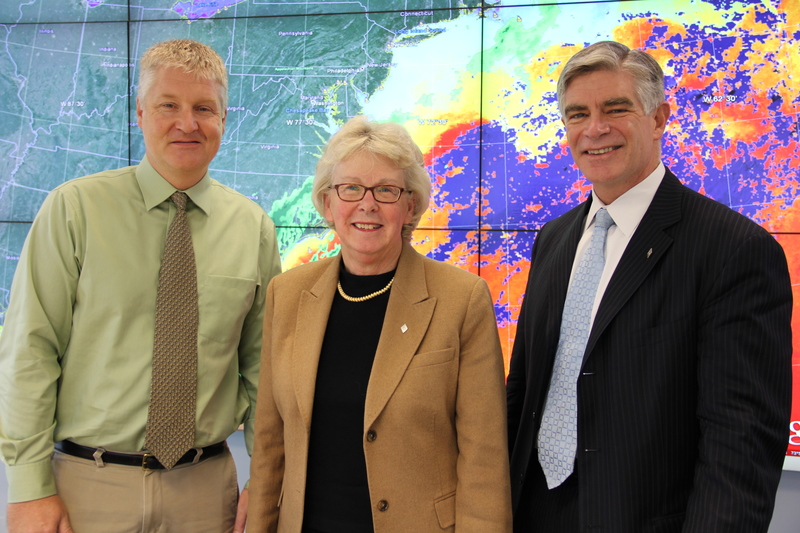

Joining him for our meeting were Nancy Targett, dean of the College of Earth, Ocean and Environment, and Mark Moline, director of the College of Marine Science and Policy. Andrea Boyle Tipton, director of external relations, started off by saying everything to be discussed was on the record. Refreshing.

We met in the conference room of the Otis Smith Laboratory, in front of a rectangular bank of nine connected television screens showing a colorful digital satellite image of Earth’s continents and seas. Melissa wrote an article for our Tuesday edition articulating University of Delaware directions touched on by Harker. If you didn’t get a chance to read it, you can still find it at capegazette.com.

Here are a few points from our discussion that have stuck with me.

First, Harker softened my concern that the college and university model of education is broken and unsustainable. Driving my concerns is knowledge that colleges and universities across the land are charging anywhere from $30,000 to $60,000 per year, leaving many students with crushing student loan debt.

Harker said Delaware students can take advantage of the state’s SEED program which pays 100 percent for the two-year program leading to an associate’s degree. Students who complete that program, many of them through University of Delaware classes at Del Tech in Georgetown, can then continue on to their final years at the university’s main campus in Newark. “In the worst-case scenario, when there are no scholarships or other assistance, those students will pay less than $50,000 for a University of Delaware degree. We think that’s affordable and a great value because of the caliber of education we offer,” said Harker. “We want to keep it that way.”

He said the university is seeing a big increase in the number of Delawareans opting to stay at home for their education. “In our most recent class that entered in September, we enrolled 400 more freshmen than we wanted. More took our offer than we expected. But that’s OK. We’re dealing with it.”

Harker said University of Delaware accepts 90 percent of the students who apply. Of those who start out in the two-year associate’s degree program, 60 percent graduate and move up to Newark to finish their bachelor’s degree.

Does that mean there’s pressure to add a downstate, four-year residential program? Not really, said Harker. “I’m sure people will find this surprising. We did a survey in southern Delaware gauging support for a four-year residential program downstate. We found that parents want their students to stay close to home but the students want to go away. There’s just no demand to support it at this time.”

Undergraduates studying in Lewes

Targett noted that for the past few years, up to 20 undergraduate students have been spending a semester in residence at the university’s Lewes campus studying environmental and marine science. “They stay in the Daiber housing complex on Sussex Drive. Here they have access to the ocean and bay, boat time, laboratories and our faculty. And they can still attend their on-campus classes through iTV. It’s a very popular program,” said Targett, “and when they get back to the main campus they’re bursting with ideas.”

At the global level, Harker said University of Delaware, through engineering and environmental technologies, is helping to “bend the curve” to help ease the pressure on natural resources. He said the university is also involved in the development of social and economic development policies to find solutions for societal issues. “If you think the oil wars have been bad, wait until you see the fights over water as the world population expands.” Desalination research receives lots of attention.

He said the university’s College of Agriculture continues to focus on increasingly sustainable crops and, like many other departments at the university, is staying focused on “bending the curve” on global warming.

Diverse comes to mind. Harker noted - near the end of our interview and in the realm of dealing with global warming - that work is also underway on developing heat-resistant chickens. That’s not to keep them from roasting in an oven. It has to do with helping them survive in a warmer world. “Fewer feathers around their necks,” he said. “We have many portfolios of activity.” Classic understatement. Seriously.