Flesh-eating bacteria found in Delaware Bay

Scientists say rising water temperatures associated with climate change have resulted in the arrival of a flesh-eating bacteria in the Delaware Bay.

Published June 18 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the study argues that over the past three decades, climate change has resulted in higher sea surface temperatures in many regions of the United States.

“These changes have resulted in longer summer seasons and are associated with alterations in the quantity, distribution, and seasonal windows of bacteria in marine ecosystems, including Vibrio species,” said the report, written primarily by Madeline King, assistant professor of clinical pharmacy, and Lucia Rose, clinical pharmacy specialist, of the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia.

The study said Vibrio vulnificus infections occur through breaks in the skin or through intestinal infections after consumption of seafood. The report said either type of infection can lead to bloodstream infections. Whether through wound or intestinal infection, once a bloodstream infection occurs, patients are at a high risk of death, particularly patients with immunosuppression.

The study says Vibrio vulnificus is endemic along the southeastern U.S. coast, living in brackish, high-salinity waters with surface temperatures above roughly 55 degrees. Cases of the infection have also been reported from the Chesapeake Bay, but are rarely reported from the Delaware Bay, which is farther north and slightly cooler. In the eight years before 2017, only one case of Vibrio vulnificus was reported, the study found.

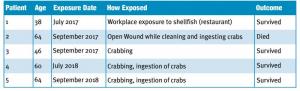

In 2017 and 2018, the study cites five cases that occurred after people were exposed to bacteria in the Delaware Bay.

Patient 1 was a 38-year-old man with untreated hepatitis B who worked at a seafood restaurant in New Jersey, but he denied exposure to crabs or the Delaware Bay. He had infected skin removed and later underwent skin grafting.

Patient 2 was a 64-year-old man who cleaned and ate crabs caught in the Delaware Bay. He was already suffering from untreated hepatitis C; his condition worsened rapidly, and he ultimately died.

Patient 3 was a 46-year-old man who, the report says, contracted the bacteria while crabbing in the Delaware Bay. He had type 2 diabetes and was morbidly obese. He survived, but his large residual wounds required skin and tissue grafting.

Patient 4 was a 60-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who was frequently in contact with crabs, including crabbing in the Delaware Bay. On the day before admission, the report said, he ate a dozen crabs. He survived, but all four of his limbs required amputation.

Patient 5 was a 64-year-old man with untreated hepatitis C, alcohol abuse and arthritis. He ate crabs, and he injured his right leg with a crab trap from the Delaware Bay. A significant portion of the skin from his right hand was infected and removed, but otherwise he was OK.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, vibriosis causes an estimated 80,000 illnesses and 100 deaths in the United States every year. The federal agency, which falls under the Department of Health and Human Services, says people with vibriosis become infected by consuming raw or undercooked seafood, or exposing a wound to seawater. Most infections occur from May through October when water temperatures are warmer.

The CDC says most people become infected by eating raw or undercooked shellfish, particularly oysters.

To reduce the chance of getting vibriosis, the CDC recommends not eating raw or undercooked shellfish, such as oysters. The agency says a person with a wound should avoid contact with saltwater or brackish water, or cover the wound with a waterproof bandage.

King and Rose said the main objective of the report was to alert clinicians of the potential risk.

“We believe that clinicians should be aware of the possibility that [Vibrio] vulnificus infections are occurring more frequently outside traditional geographic areas,” wrote King and Rose.

DNREC does not test for Vibrio

In a prepared statement July 3, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control spokesman Michael Globetti said there have been no reported cases of Vibrio in Delaware in 2019. He said a recent batch of beach swimming advisories issued by the department’s Recreational Water Program has been due to elevated levels of Enterococcus bacteria, an indicator bacteria found in the gut of warm-blooded animals. He said recreational waters are tested only for Enterococcus, based on federal Environmental Protection Agency waterquality criteria.

Globetti said DNREC tests the water because after heavy rainfall and rough surf, Enterococcus can be washed into nearshore waters where people swim. He said Enterococcus bacteria originates primarily from wildlife, including large shorebird populations.

“DNREC’s recreational water advisories are not meant to cause alarm, but rather to give the best information to the public to decide whether or not they want to recreate in bodies of water for which the advisories are issued,” said Globetti.

Globetti said Vibrio bacteria is not linked to Enterococcus. “Vibrio are naturally occurring and found in all marine waters. They are not associated with fecal contamination or sewage,” he said.

To check if a water advisory has been issued along the Delaware shoreline, go to https://apps.dnrec.state.de.us/RecWater/.

Reporter Melissa Steele contributed to this article.

Chris Flood has been working for the Cape Gazette since early 2014. He currently covers Rehoboth Beach and Henlopen Acres, but has also covered Dewey Beach and the state government. He covers environmental stories, business stories and random stories on subjects he finds interesting, and he also writes a column called Choppin’ Wood that runs every other week. He’s a graduate of the University of Maine and the Landing School of Boat Building & Design.