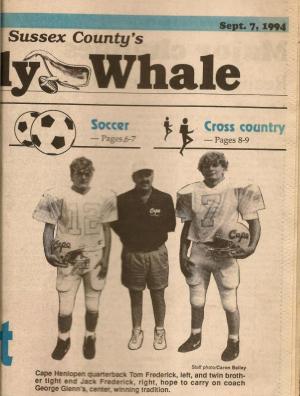

Tom Frederick: a Cape kid to the core, his later life a struggle

Going home! It’s Homecoming, 1994, Cape versus Milford. Quarterback Tom Frederick drops back and hits his twin brother Jack in full stride on a slant pass. Jack corrals the ball and accelerates untouched the next 45 yards for a touchdown. On Cape’s next possession, coach George Glenn, who always professed “I’m not that smart,” runs motion away from the formation. The defensive corner loosens up and tight end Jack Frederick runs a straight streak down the seam and Tom hits him in the numbers for a 50-yard touchdown. All-state running back Sean Bradham shouts loudly, “We are in good shape tonight! The Fredboys have brought their A game.”

That spring, Cape is hosting Salesianum in lacrosse; the best two teams in the state are slugging it out. The game goes into sudden-death overtime. Midfielders Tom and Jack are raising a ruckus, dropping bodies and accumulating penalty minutes. Tom sends a bouncer from out front that beats the goalie for the victory. Cape talks smack, that was their character.

That May, 1995, on a humid, blue-black, cloud-covered and rumbling evening, Cape played Sallies for the state title at A.I. DuPont, their very first appearance in the state championship game. The game was “thunderous interruptus,” interspersed with a first-quarter bench-clearing brawl. Sallies won 12-6, but Cape got their money’s worth, and the players from football and lacrosse would stay “boys into manhood.”

But Tom got derailed, went into the ditch of bad decisions. It always starts with alcohol and can move to other things. He was the leading edge of the addiction epidemic. The blue-eyed and blond-haired quarterback from a small town with a family who loved him damaged his brain over time and couldn’t find his way back.

Tom and Jack were Cape’s first lacrosse players to go the Division I next level. They played for the UMBC Retrievers. The spring of Tom’s freshman year, opening night in Catonsville, I looked out and he was on the face-off line with a long pole against the University of Virginia. The Fred twins, who played every sport growing up in the small town of Lewes, had made it. Teammates called them the Hanson brothers from the movie “Slap Shot.”

Tom slowly spiraled downward; a smart athlete who could read on run became dumb decision guy. Substances and combinations, getting ripped does not take you only higher, think of the spokes on a wagon wheel, and you are them all. The brain is the hub and creates its own realities.

On Monday at noon, I gave Tom the OK to drive Darby dog to Rehoboth in my 17-year-old Tundra. I trusted him to do that, and he seemed absolutely fine.

An hour later on the way back home heading north he crossed the grassy median into southbound traffic and was killed. “We” were first thankful no one else died in the accident. Tom, a nice person but a tormented soul, had left the planet. My wife Susan sat in a chair inside the grief room at Beebe hospital, among a nuclear family totally numb.

“Tom was always his own victim,” his mother said. “It is just so incredibly sad.”

The current term is “dual diagnosis.” Which comes first, the addiction or the mental illness? There is no doubt they interact. Sports and sobriety is the dual diagnosis that gives athletes the best chance of a long and happy life.

We just have to get there, and we all have to try harder.